The Pioneering Spirit of “The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon”

Cover art from: The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon

As Mushi Productions began exploring new styles with A Certain Street Corner Story, a growing dissatisfaction brewed among Toei Animation staff. Discontent with the restrictive creative environment and outdated animation techniques of The Tale of the White Serpent and Arabian Nights: Sinbad’s Adventures, labor union movements gained momentum. Following Sinbad’s Adventures, these movements led to a consensus across Toei’s departments: their next project would honor Toei’s traditional feature film style while incorporating the latest techniques to create a groundbreaking animated movie.

Genesis of a Classic

This new project drew inspiration from the classic Japanese myths and historical accounts found in the Kojiki. Initially titled Rainbow Bridge, it was later renamed The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (わんぱく王子の大蛇退治), often referred to as The Little Prince. The film was directed by newcomer Yugo Serikawa (credited as “Director”), with Yasuji Mori as the animation supervisor (credited as “Original Drawing Supervisor”). Notably, Isao Takahata, who would later become a renowned director, served as an assistant director on this film. However, it was the art director, Reiji Koyama (credited as “Art”), who played a pivotal role in shaping the film’s overall aesthetic.

Koyama’s Vision: Form Over Mass

Koyama, with a background in Japanese painting from an art university, possessed a remarkable talent for flat design. During the film’s pre-production, Koyama advocated for emphasizing “form” (フォルム) over “mass” (マッス), prioritizing flat shapes over three-dimensional depth. This concept, along with Koyama’s overall design for various segments, significantly influenced the character designs and animation style. This marked a rare instance in early Toei animation where art direction heavily impacted the animation and direction.

Character Design and the Dawn of a New Style

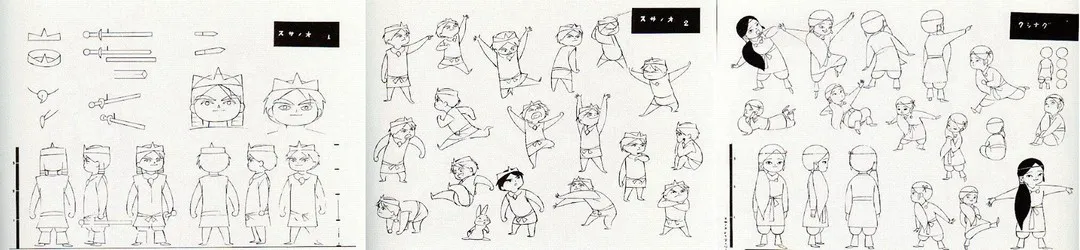

Serikawa and Mori, embracing Koyama’s vision, delegated character design to individual animators, encouraging them to take ownership of the key animation for their respective characters. Mori, already aware of the innovative design principles of the UPA style (United Productions of America), which he had begun to incorporate in Kitty’s Studio, eagerly embraced this new direction. Fresh from his experience on The Tale of the White Serpent, Mori was eager to innovate, finding common ground with Koyama. He personally designed the protagonist, Susanoo, his family, and Princess Kushinada. These designs, in stark contrast to the realistic styles of the past, heavily incorporated geometric shapes, resulting in a more simplified and stylized aesthetic.

Susanoo and Kushinada character designs by Yasuji Mori for The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

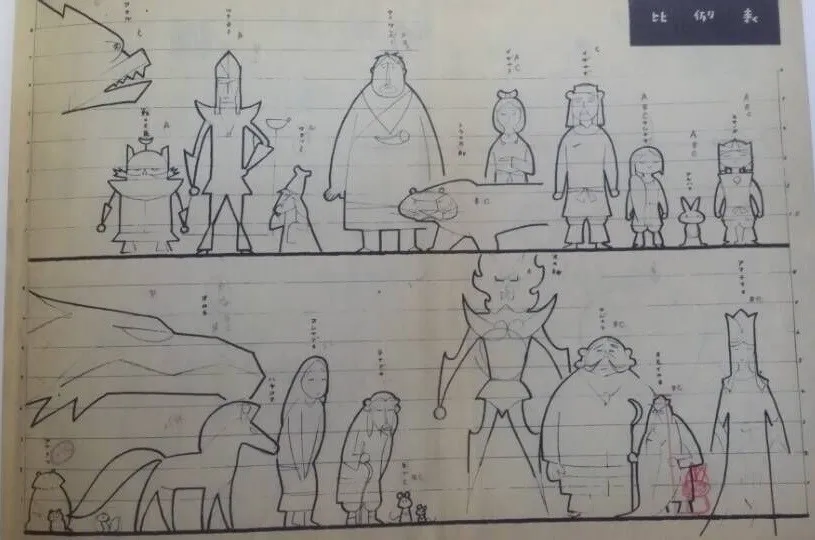

The Birth of the Animation Supervisor Role

Besides Mori, other animators contributed to the character designs: Masatake Kita designed the original concept and animation for Tiger Boy, Hideo Furusawa designed the monstrous fish, Yoichi Kotabe designed the divine horse, Daikichiro Kusube designed the fire god, Masao Kumakawa designed Amaterasu, Reiko Okuyama designed Izanagi, Jun Nagasawa designed Ame-no-Uzume, and Yasuo Otsuka and Sadao Tsukioka designed the Eight-Headed Dragon. As previously noted, Toei’s feature films, since The Tale of the White Serpent, had struggled with inconsistent art styles due to different animators. To mitigate this issue, with over a dozen animators working on The Little Prince, Mori became the first animation supervisor in Japanese animation history. His role was to unify the art style and proportions of the various characters. Mori also noted that the creation of the animation supervisor role was partly inspired by Koyama’s influence as art director. Animators felt the need to elect a representative to communicate with the director, similar to how Koyama influenced directorial decisions.

Character proportion chart by Yasuji Mori for The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

Animation Techniques: A Blend of Full and Limited Animation

In terms of animation, Mori’s sequences primarily featured detailed full animation, while other animators experimented with limited animation techniques. This was particularly evident in the rapid movements of the rabbits and the afterimages used in Susanoo’s battle scenes. Okuyama’s Izanagi sequence and Nagasawa and Norio Hikone’s Ame-no-Uzume dance sequence also incorporated limited animation, creating a strong sense of flatness and dynamism through quick pose changes and a lack of in-between frames.

Examples of afterimage techniques in The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

Animation by Reiko Okuyama? in The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

Serikawa’s Direction: A New Wave in Animation

Beyond the artistic and animation innovations, Serikawa challenged Toei’s traditional direction. Coming from a family involved in a small film company, Serikawa was immersed in cinema from a young age. He studied German literature at Waseda University, writing his thesis on Hermann Hesse. This influenced his directorial style, incorporating the theme of “eternal femininity” (Ewig-Mütterliche) found in the works of Goethe and Hesse. After joining Toei during the production of The Tale of the White Serpent, where he assisted with storyboarding and served as assistant director due to Yasuji Yabushita’s illness, Serikawa was appointed director of The Little Prince. He envisioned the film as a “new wave in modern animation,” aiming to revolutionize the industry like the French New Wave had transformed cinema.

Challenging Traditional Cinematography

Traditional Toei animation, similar to Disney, primarily used medium, full, and long shots, relying heavily on long takes and lateral movements reminiscent of stage performances. Directors like Yabushita often incorporated animator feedback, leading to frequent changes in shot content and effectively centering the film’s production around animators like Mori and Daikuhara. Serikawa, however, dared to experiment with different camera angles, such as low-angle and high-angle shots, increased the use of close-ups and extreme close-ups, and emphasized the role of montage. For example, the average shot length (ASL) in the climactic battle scene of Magic Boy was approximately 4 seconds, while in The Little Prince, it was only 2 seconds.

A Shift Towards Director-Centric Filmmaking

The difference between the two styles mirrored the distinction between the seamless editing style prevalent in Hollywood’s Golden Age and the disjointed editing found in Soviet and French cinema. The former emphasized “invisible” editing, serving the actors’ performances, while the latter used editing to construct a cinematic time and space distinct from real-life, generating emotional undertones rather than focusing solely on the actors. While still respecting the animators, Serikawa’s directorial approach marked a shift from animator-centric to director-centric filmmaking in Japanese animation. Takahata, as his assistant director, would further develop this director-centric approach in The Little Norse Prince Valiant.

The Battle Against the Dragon: A Showcase of Serikawa’s Style

The climactic battle between Susanoo and the Eight-Headed Dragon in The Little Prince exemplifies Serikawa’s directorial style. Under his guidance, Otsuka and Tsukioka fully utilized the vast sky, employing vertical movements and compositions with depth. Takahata described this as “successful but naive.” The shots of Susanoo flying through the dragon’s heads towards the screen (animated by Otsuka), the low-angle shot of Titanbo throwing a javelin to Susanoo (animated by Tsukioka), and the shots of the dragon heads chasing Susanoo along the cliffside with their shadows appearing first (animated by Tsukioka) represented a groundbreaking awareness of spatial depth in Japanese animation.

Director: Yugo Serikawa, Animation: Yasuo Otsuka, Sadao Tsukioka, The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

Pioneering Editing Techniques

Serikawa’s editing techniques had a profound impact on subsequent Japanese animation. As assistant director on The Tale of the White Serpent, he had already begun using insert shots and cutbacks. In the sequence where Anju confronts the giant spider, the tension is built by alternating between shots of Anju and the spider (cutbacks) and tracking up shots. The action of Kuzushimaro gripping his sword is repeated twice to emphasize his determination.

Assistant Director: Yugo Serikawa, Animation: Yasuo Otsuka, The Tale of the White Serpent (1962)

According to Otsuka, Serikawa would ask him to draw “extra” shots for insertion during editing. Initially, Otsuka didn’t understand Serikawa’s intention and resisted, but he understood after seeing the edited version. The battle with the dragon in The Little Prince is filled with these “extra” shots. In the scene where Susanoo descends rapidly to attack the first dragon head, the camera alternates between Susanoo and the dragon, repeatedly showing close-ups of both. After the javelin is thrown, a close-up of the javelin is inserted – undoubtedly one of the “extra” shots Otsuka mentioned.

Director: Yugo Serikawa, Animation: Yasuo Otsuka, Sadao Tsukioka, The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

When Susanoo attacks the second dragon head, the arm motion of throwing the javelin appears twice in adjacent shots, demonstrating overlapping editing. Unlike the simple repetition of the sword grip or the rapid descent, the throwing motion is achieved by overlapping a portion of the action (5 frames) between two shots. The last part of the previous shot is repeated at the beginning of the next, making it seem as if Susanoo swung his arm twice, adding force to the javelin throw.

Example of overlapping editing in The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

Serikawa also used multiple angles and perspectives with rapid editing to depict the same action. For example, Susanoo’s leap across the mountain crevice is presented from three different camera angles. The climax, where Susanoo raises the Sword of Kusanagi to kill the final dragon head, uses medium close-up, close-up, and extreme close-up shots. The pacing of 1.3 seconds, 0.7 seconds, and 3 seconds makes the final extreme close-up shot feel particularly long, creating a momentary pause in time and emphasizing Susanoo’s determination in his final strike. This technique is commonly used in later Japanese animation to highlight decisive moments.

Example of using multiple angles and perspectives to depict an action in The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1963)

Reconstructing Time Through Editing

By using cutbacks, repeated shots, overlapping editing, and multiple angles with rapid editing to depict the same action, Serikawa effectively reconstructed time. The extensive editing made the brief action seem prolonged in the viewer’s mind. This was a first in Japanese animation, and possibly in world animation. While these techniques were not uncommon in live-action films, Serikawa was the first to apply them to animated films.

In Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), the famous Odessa Steps sequence used rapid editing, repeated shots, and overlapping editing to extend the confrontation between soldiers and civilians to nearly 8 minutes. In the climax, the shots of the woman and the baby carriage are repeatedly interrupted, and each time the camera returns to her, she is further back, extending her fall through montage. Eisenstein replaced the linear time of the actual action with the viewer’s psychological and emotional time, creating intense tension. In post-war cinema of the 1950s, particularly in action genres like American Westerns and Japanese samurai films, these techniques were frequently used to enhance the drama of fleeting moments, such as cowboy duels and samurai sword clashes.

Serikawa’s techniques may have originated from post-war action films, tracing back to Eisenstein. His methods were widely adopted in Japanese animation, becoming even more radical, stylized, and formulaic. For example, in baseball anime like Star of the Giants, pitching scenes often feature a wind-up, a close-up of glowing eyes, an arm swing, a close-up of the ball in the air (possibly using overlapping editing), and the ball flying towards the batter. Similarly, directors like Osamu Dezaki would repeat a push-in/push-out shot or a panning shot three times to prolong the moment and heighten the sense of urgency.

A Landmark Achievement

The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon is a culmination of Toei Animation’s direction, art, and animation. It established the animation supervisor system in Japan, began exploring vertical movement, and pioneered editing styles distinct from traditional Western animation films like Disney. It stands as one of Toei’s most significant animated feature films, holding immense historical importance. With this film, Toei finally rivaled Disney in terms of film quality while establishing its unique style.

Unlike previous films like The Tale of the White Serpent and Magic Boy, which received modest international recognition, The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon garnered widespread acclaim, securing Toei’s place on the world stage. In 2003, the Tokyo Laputa Animation Festival ranked The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon tenth in a list of “150 Best Animated Films” selected by 140 international animators and film critics, making it the third-highest-ranked Japanese animated film (behind two works by Hayao Miyazaki). Renowned American director Genndy Tartakovsky cited The Little Prince as a primary inspiration for the direction and design style of Samurai Jack, and Irish director Tomm Moore has acknowledged the film’s significant influence on the style of Song of the Sea.

Despite its critical acclaim, The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon was sadly the last film to involve the entire Toei staff. After reaching this peak, Toei Animation’s feature films began to decline as the era of television animation approached. (To be continumēshon ni Okeru Ugoki no Kenkyū