Once upon a time, or not so long ago in a galaxy not so far away, the Wang family was dreading an audit: their immigrant laundromat was causing more trouble than income, and a visit to the tax office during Chinese New Year didn’t exactly lift their spirits. Besides external disruptors in the form of the bureaucratic executioner Deirdre (perhaps Jamie Lee Curtis’s most unusual role), the family is also torn by internal conflicts. The elderly grandfather (James Hong) is always looking for another reason not to be proud of his daughter (Michelle Yeoh’s triumph) and her husband (Jonathan Ke Quan): escaping their homeland for a foreign country was only good in theory. Evelyn herself doesn’t learn from her elders’ mistakes, and she finds fault with her own daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu): from her weight to her choice of partner. Chaos reigns everywhere even before the opening of the universe’s breach: “everything everywhere all at once” seems like a forced way of life and Evelyn’s motto, not just the film’s title.

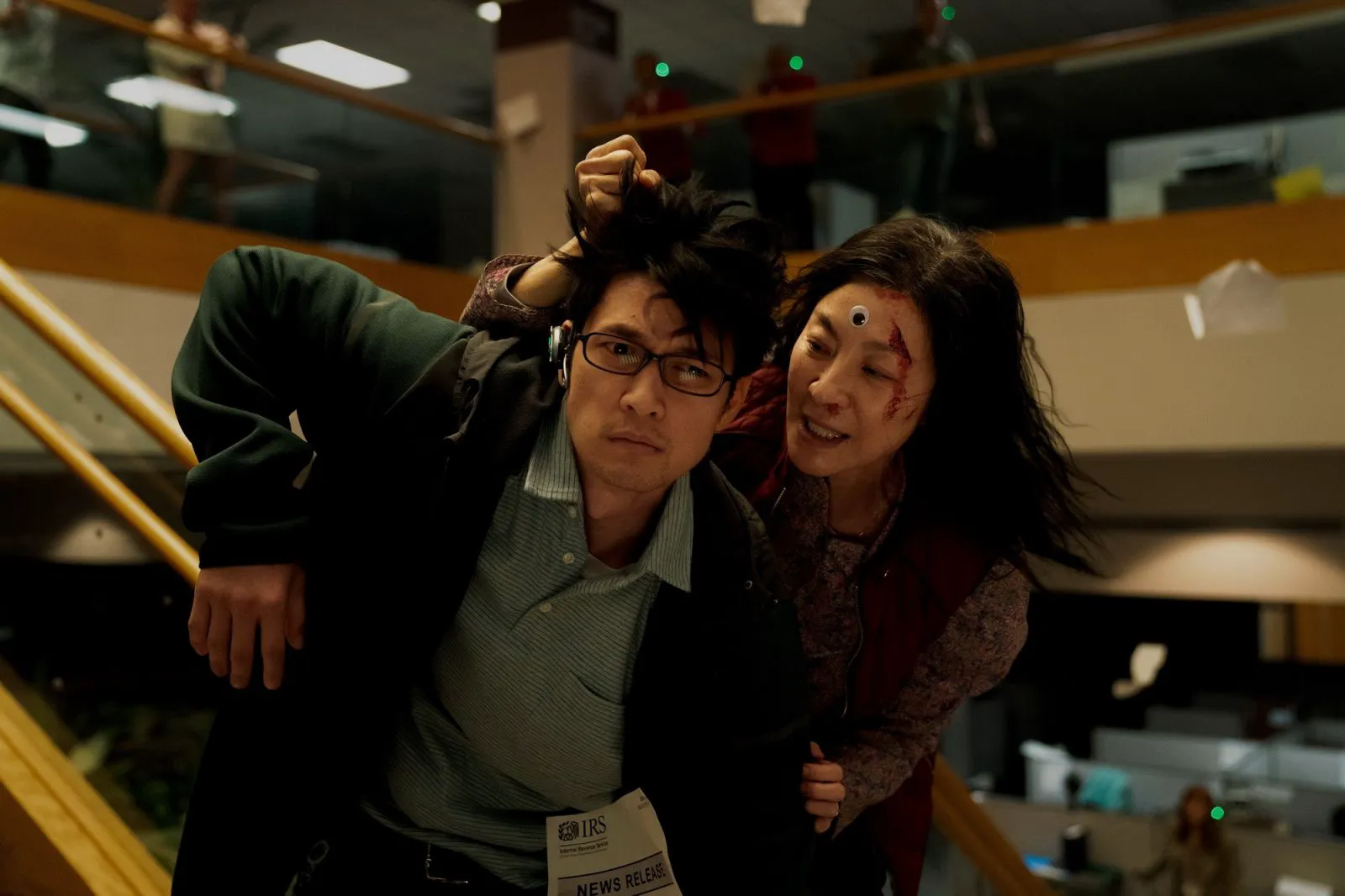

Michelle Yeoh as Evelyn in a still from “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

Over the past five years, directors Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert have proven two things: their cinematography can easily enrage an unprepared viewer, and it’s better to be together than apart. After the wacky comedy (or survival horror, who knows) “Swiss Army Man,” some of the audience branded them as charlatans and holy fools from the indie world, while others desperately awaited their next film. “The Death of Dick Long” happened just two years later, but Scheinert without Kwan clearly lost charisma and riot of mise-en-scène. Now, a natural continuation of their joint experiments on the edges of the impossible is taking place. At first, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is a chamber film: almost all the action will take place in the tax office – dreary, stubbornly beige, and filled with the rustling of papers. A place by nature and mechanics soulless and airless: documents rule here, not people. But not for those who can read between the lines: everyone is in danger, you need to hurry to a parallel world (or bring it here) before the universe collapses into a giant black bagel of existence.

Michelle Yeoh as Evelyn in a still from “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

There’s no point in retelling the mechanism of transitions – the technique is so absurd and at the same time impenetrably logical that it’s better to see with your own eyes how the undoubtedly great Michelle Yeoh looks for flaws and fine print in the theory of probability. Psychologists would like it: the starting point of each new jump into another life is getting out of your comfort zone – do something no one expects. Uploading other Evelyns from the multiverse of madness into her tax reality – a famous actress, a kung fu master, a chef, a wife, and a mother – the laundromat owner comes to the disappointing conclusion: the tale of missed opportunities ended with her becoming the worst version of herself. But even this is not a fiasco – being the first from the end is also an achievement, and failure is a starting point for victory.

Stephanie Hsu as Joy in a still from “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

Pop Culture Extravaganza

Reflections on binary choices, alternative universes, the search for a destined path, and other existential troubles became an excuse for Kwan and Scheinert to open a chest of pop-cultural treasures and shake out their entire sequence. If everything is everywhere all at once – a method of existence of the existing and the cosmic foam of being, then the cinematic language should be arranged in the same way. From the endurance and uncompromising nature of kung fu action films to the meditative tenderness of Wong Kar-wai’s evenings, from the lost shores of Indiana Jones (Evelyn’s husband is that boy from “Temple of Doom”) to the reboots of the Wachowskis’ “Matrix” or even “Ratatouille” and Kubrick’s “Space Odyssey” – citation remains a method, frozen a step away from self-purpose. Souvenirs from the edge of cinema also play with perception: some scenes are damn funny and absurd, as “Swiss Army Man” bequeathed, while during others it’s hard not to shed a tear. But Kwan and Scheinert’s delightful and fearless fantasy turns out to be not so much genre acrobatics as a soul-saving film about how you don’t choose your parents. However, like children. And no matter how many universes exist, differences are not smoothed out: even if you are just two stones by a cliff, there will always be something to argue about.

A Film for Everyone

The final volley of confetti before the curtain about unconditional love for relatives might seem exhausted and hackneyed in any other circumstances and coordinates. But today, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is probably exactly the film that everyone needs, now and everyone. Its absurdity, elevated to a principle, proves once again that nothing ideal exists, no matter how many universes you have to go through, and the most precious thing is already nearby. It only remains to finally learn to love each other, as Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert love cinema: sincerely, mutually, and forever.