Akira: A Cyberpunk Anime Masterpiece

A classic blockbuster sci-fi anime about teenagers with psychic abilities.

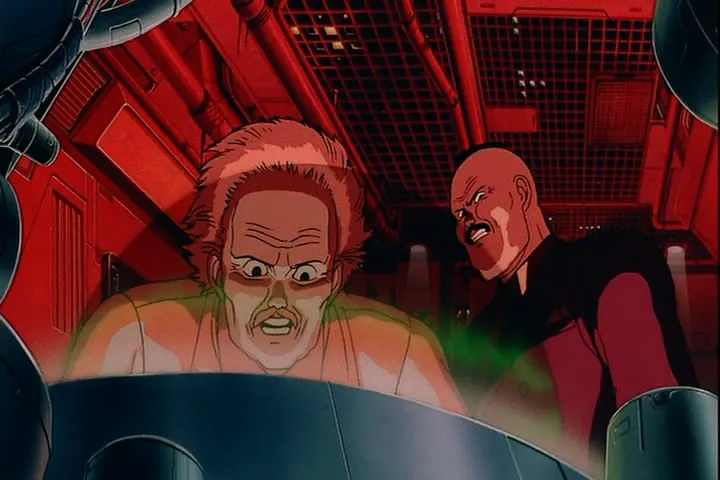

In 1988, Tokyo was destroyed by an explosion that marked the beginning of World War III. Three decades later, a new metropolis, Neo-Tokyo, has been built on the ruins of the Japanese capital. During a clash between youth biker gangs, teenagers stumble upon a strange boy with gray skin and senile wrinkles, who is being pursued by an army unit. While trying to escape, the child uses telekinesis, which activates the hidden extrasensory abilities of a biker named Tetsuo. Army medics take both to their base and begin experimenting on Tetsuo. Meanwhile, Kaneda, the leader of the bikers and an old friend of Tetsuo, befriends a girl from an anti-government rebel group and prepares to free his comrade, who is rapidly turning into a superman.

Akira’s creator, Katsuhiro Otomo, is a big fan of the Japanese comic series “Iron Man No. 28” from the 1950s and 1960s, one of the early representatives of the “big robots” genre. Therefore, the film is scattered with references to “Iron Man”: the names “Shotaro Kaneda” and “Shikishima”, the number 28, and so on.

Among the classic anime films, “Akira,” released in 1988, holds a special place. It is not just a milestone achievement of Japanese animation; it is a film that largely created the international anime fandom. When viewers in America, Europe, and later Russia saw it, they understood that they would not see anything like it from their countries’ animators in the coming years or even decades. “Akira” convinced them to take a closer look at the mass culture of the country that produces “cartoons” where a dog is shot point-blank in the seventh minute, a girl is almost raped in the 28th minute (after having her clothes torn off), and a metropolis is blown to smithereens in the finale. No Little Mermaids here!

Beyond the Violence: Exploring the Depths of Akira

In all fairness, “Akira” is not just about violence, which is brutal and grandiose even by the standards of modern computer-generated blockbusters (let alone films of the 1980s!). Comic artist Katsuhiro Otomo experimented with the ideas that formed the basis of “Akira” in smaller projects for several years before deciding to start publishing his most significant and epic work in 1982. His experiments paid off handsomely – “Akira,” published until 1990, turned out to be not only a long (about 2000 graphic pages) but also an all-encompassing epic in the “dark futurism” genre, which is usually called “cyberpunk.”

The latter word is not entirely suitable for “Akira” – computers and virtual reality do not play a significant role in its narrative. However, “Akira” is definitely “punk,” a cynical and pessimistic view of the future in which progress empowers villains and throws everyone who was not born with a silver spoon (or golden chopsticks) to the wayside. Corrupt authorities, police and military abusing weapons, sadistic experiments on children, a thoroughly rotten education system, rampant youth gangs, flourishing religious cults… Neo-Tokyo is technically advanced, but only a masochist would want to live in such a place.

Innovative Animation Techniques

Before “Akira,” voice actors in the anime industry were recorded after the animation was completed. Therefore, the voices of the characters were only approximately synchronized with the movements of the lips on the screen. “Akira” was made in reverse order – first the voices were recorded, and then the mouths were drawn to make the synchronization as accurate as possible.

Parallel to working on the comic, Otomo worked on several animation projects, and when he was offered to adapt “Akira” (which was far from finished at the time – a common practice for Japanese animation), the artist insisted that he write the script himself and direct the uncompromising feature film. Knowing from the inside how the anime industry works, Otomo was very afraid to give his creation into the hands of others, possibly shoddy ones. To secure the requested record budget of 1.1 billion yen (11 million dollars), leading Japanese media companies (publisher Kodansha, toy and video game manufacturer Bandai, distributor Toho, television company Mainichi Broadcasting System, anime studio Tokyo Movie Shinsha, and others) had to create a committee-consortium specifically for the creation of “Akira.” Over time, such committees became common practice.

(1).jpeg)

Some fragments of “Akira” were drawn using computers. In particular, a three-dimensional oscilloscope was created on a computer, showing the pulsation of Tetsuo’s parapsychic field in the film.

Akira vs. Blade Runner: A Comparison

When you compare the resulting film with the main Western cyberpunk masterpiece of the 1980s, “Blade Runner,” the first thing that strikes you is how much more expressively free Otomo’s vision is than Ridley Scott’s. Where Scott only hints at the world of the future and invites viewers to speculate on the fragments shown on the screen, Otomo’s artists unfold detailed panoramas and tirelessly change landscapes and settings. The battle scenes of the two films are not even comparable. “Akira,” as already mentioned, is action at the level of modern blockbusters, and against the background of its city-shredding clashes between the army and the super-powerful telekinetic Tetsuo, both “Blade Runner” and “Terminator 2,” filmed a decade later, pale in comparison. At the same time, the film does not suffer from unconvincing special effects, since everything in it is equally drawn and equally convincing (or unconvincing – depending on how seriously you take animation).

.jpeg)

Changes from the Manga

Turning the comic into a film, Otomo got rid of most of the political “twists and turns” of the original and several key characters, who either disappeared altogether or appeared only in tiny cameos (in particular, a politician nicknamed “Rat” and the leader of the religious cult Miyako). Even the title character Akira – a child whose parapsychic power turned him into an immortal deity and destroyed old Tokyo – appeared in only a few scenes. This made the ending of the film disconcertingly “deus ex machina” (in the literal and figurative sense of the word), but it allowed the action to focus on three main characters – young bikers Tetsuo and Kaneda, and Colonel Shikishima. The latter is ready for anything, even bloody crimes, to protect Neo-Tokyo from threats, some of which he himself created. It is interesting to note that this character turned out to be almost the most complex, humane, and charismatic in all of “Akira.” However, this is typical for cyberpunk – remember Roy from “Blade Runner” or Agent Smith from “The Matrix.”

.jpeg)

Friendship and Untapped Potential

For Otomo, “Akira” the film has always been primarily a story about friendship, which is subjected to a monstrous test when the rapidly growing superpower turns Tetsuo into a madman and a murderer. The confrontation between the antihero and Kaneda is all the more bitter because they are both orphans, and they have no one closer than each other. However, the fact that the superpower drives Tetsuo crazy and almost completely subordinates him makes the heroes’ feud dramatic and emotional, but not too interesting. Sane opponents (even sociopathic ones) would be more engaging. And, in addition, when you think about what is happening in the film, you realize that the real main theme of “Akira” is not the friendship of the heroes and not the danger of science playing with fire (a common plot for Japan, which was subjected to two atomic strikes), but the energy hidden in children and adolescents that does not find a creative outlet.

The latter is worth dwelling on in more detail, since reviews of “Akira” usually do not notice this. At best, they draw an obvious parallel with Stephen King’s “Carrie.” However, in the American’s book, sexual energy, constrained by ultra-conservative upbringing, breaks through catastrophically (of course, we are talking about the subtext of “Carrie,” not the vicissitudes of the plot). “Akira” critically hints at the social structure of Japanese society, which guaranteed young people that they would make a career not thanks to their talents, but by seniority. A great offer for modest and obedient people, but a real torture for even slightly ambitious guys. Especially for those who did not have a “hairy paw.”

It is not surprising that in 1982, when work began on “Akira,” the number of youth biker gangs reached its peak. Crashing or going to jail seemed more pleasant than making a lot of effort to study and then working for years and decades in an insignificant position and waiting for senior employees to retire. The energy of youth, which could serve society, found criminal or, at best, meaningless outlets, and a thoughtful person had reason to despair and express his feelings in an epic about lost guys whose unclaimed inner strength destroys cities.

This was just one of the many themes touched upon in the film, and “Akira” is so reminiscent of a thick soup in which a spoon stands. The picture is so saturated with events and characters that it is almost impossible to understand it from the first viewing. When, after several repetitions, you begin to understand most of what happened, you notice that the tape leaves some significant plot questions unanswered – usually because these answers are in the comic.

Life has shown that this was an excellent bait for the nascent foreign anime fandom. Because some fans tried to find answers by frame-by-frame viewing, while others looked for friends in Japan and found out from them what was said in Otomo’s printed work, which was inaccessible outside the country. Both were much easier and more fun to do in companies than separately, and the newly minted fans of “Akira” had a good reason to unite in clubs.

Is Akira a Masterpiece?

Can “Akira” be called a masterpiece, given all of the above? Yes, it can. But it’s not a flawless masterpiece. It has a lot of roughness, starting with the already mentioned Deus ex machina ending and ending with the fact that Kaneda and his beloved Kei are drawn in some scenes so that they seem like twins. Nevertheless, “Akira” is an epoch-making film that set a new bar of animation and plot quality for Japanese animators, “promoted” anime in the West, and became one of the best representatives of its genre. Even now, a quarter of a century after its premiere, “Akira” can give a head start to many science fiction hits. And it offers a lot to both fans of grandiose spectacles and viewers who like to reflect on what they have seen. So if you haven’t seen it yet, you’ve missed a lot. Especially if you appreciate uncompromising and unpredictable cinema.