The Cyberpunk Prophecies of Mamoru Oshii: More Music Than Novel

Movies should resemble music more than novels.

Editor’s Note:

With the classic cyberpunk film “Ghost in the Shell” finally making its debut in mainland China this week, we’re taking a look at this iconic work and its director, Mamoru Oshii, often dubbed the “Original Work Destroyer.” Due to space constraints, this article will primarily focus on his role as an animation director.

In 1993, at the age of 42, Mamoru Oshii had just completed his anti-militaristic animated film, “Patlabor 2: The Movie.”

The film originated from the HEADGEAR creative team’s two-dimensional project. The manga portion, handled by Masami Yuuki, depicted a near-future Tokyo grappling with social issues arising from the large-scale introduction of giant robots called Labors, implemented for land reclamation projects.

Oshii was responsible for adapting this IP into a film.

Diverging from the manga’s lighthearted and slice-of-life tone, Oshii’s “Patlabor” took a sharp turn towards political thriller territory. He infused the work with his personal reflections: a critique of Japanese politics and a pessimistic view of the relationship between technology and humanity, particularly concerning Artificial Intelligence (AI).

In “Patlabor 2: The Movie,” Tsuge Gyobu utters the line: “Looking at the city from here, it’s like a mirage.”

This sentiment also resonates with “Ghost in the Shell,” as it reflects Oshii’s characteristic perspective on the metropolis. Having grown up in Ota Ward, one of Tokyo’s southernmost districts, with the expansive Tokyo Bay before him and the bustling Tokyo metropolis behind, Oshii’s unique vantage point shaped his artistic vision.

From Tokyo Bay to Cybernetic Landscapes

Born in 1947, Oshii’s mother remarried a private detective.

During the 1960s, Japan witnessed the peak of anti-establishment movements. A young Oshii, identifying himself as a “soldier,” enthusiastically participated in these movements.

However, his political fervor was soon quelled by his father.

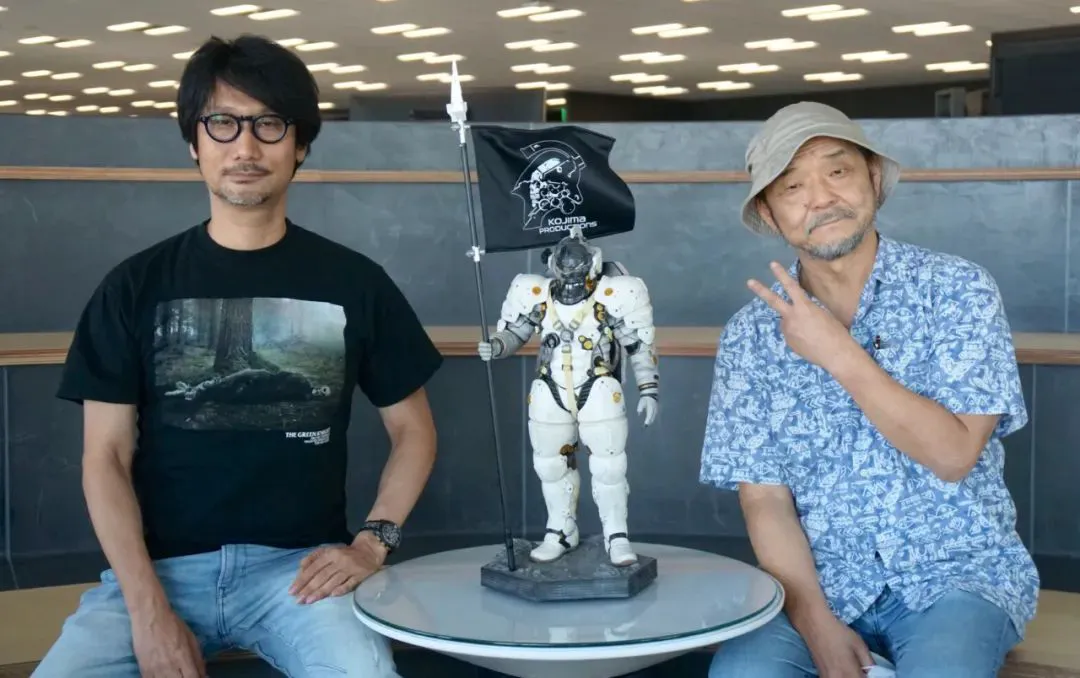

Hideo Kojima and Mamoru Oshii

In his third year of high school, a visit from the police alerted his parents to the seriousness of his involvement. Oshii was confined by his father to a mountain cabin in Daibosatsu Ridge for the entire summer, with reading as his primary, and only, form of entertainment.

During that period, literature became Oshii’s closest companion. He delved into the works of Hegel, Marx, Trotsky, Blanqui, and others in search of truth. However, it was Japanese science fiction that captivated him the most.

Perhaps driven by nuclear anxieties, a sense of “mono no aware” (the pathos of things), or the spiritual void created by rapid economic growth, Japanese science fiction of the era, unlike the generally optimistic Western sci-fi of the 60s, was filled with apprehension.

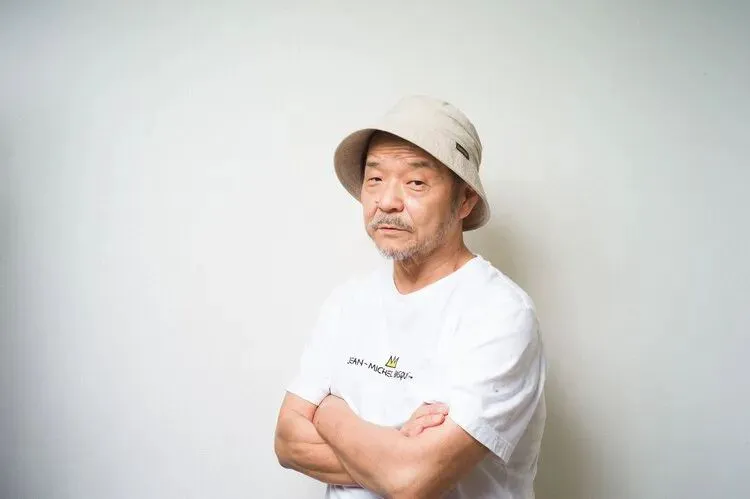

Sakyo Komatsu

Osamu Tezuka’s “Phoenix” repeatedly explored the cycle of technology and destruction, while Sakyo Komatsu’s “Japan Sinks” and “The End of the Endless River” evoked a sense of impending doom. Komatsu, in particular, had a profound impact on Oshii, who even aspired to become a science fiction writer himself.

Politics and science fiction largely shaped Oshii’s adolescent worldview, and these two elements would later become the foundation of his works.

In 1970, Oshii entered Tokyo Gakugei University and became immersed in cinema. He not only watched thousands of films each year but also founded the “Image Art Research Society.”

His obsession reached such a point that he barely attended classes during his six years at university (including a year of repeating), dedicating his time to figuring out how to make his own films.

Politics, science fiction, and cinema – the three key elements that would define Oshii’s life had converged. However, realizing these elements artistically proved to be a significant challenge.

Upon entering the workforce, Oshii, like many others, began desperately seeking employment. After numerous rejections, he finally landed a job at a broadcasting production company, only to leave after ten months due to unpaid wages.

Lost and without direction, Oshii stumbled upon a recruitment advertisement posted on a utility pole. To his surprise, it was from the renowned Tatsunoko Production, seeking staff for administrative positions.

By chance, Oshii joined this legendary studio, albeit in a menial role.

However, as the saying goes, “a golden carp does not belong in a pond.” The 1970s marked a period of rapid growth for the Japanese animation industry. With classic early anime like “Science Ninja Team Gatchaman,” “The Adventures of Hutch the Honeybee,” and “Tekkaman: The Space Knight,” Tatsunoko’s reputation grew, leading to an increase in production requests. Consequently, Oshii, who had started as a general assistant, was assigned to the business department, giving him the opportunity to showcase his abilities.

“The Adventures of Hutch the Honeybee” was once broadcasted by CCTV

In 1977, Oshii participated in the production of the anime series “Yatterman.” While not widely known, the production team involved was remarkably talented, with almost every member becoming a pillar of the animation industry.

The team included Koichi Mashimo (“.hack//Sign”), Hidehito Ueda (“Natsume’s Book of Friends”), Masami Annō (“Cooking Master Boy”), Yoshiyuki Tomino (“Mobile Suit Gundam”), and, of course, Oshii, who made his directorial debut with this project.

The Birth of the “Original Work Destroyer”

After his official debut, Oshii’s career as an animation director progressed relatively smoothly.

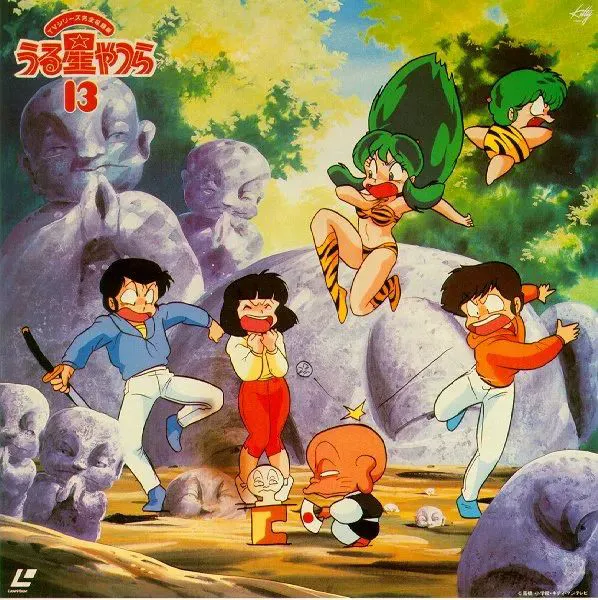

In 1981, he was responsible for animating Rumiko Takahashi’s iconic manga, “Urusei Yatsura.”

Urusei Yatsura

Oshii then personally directed two theatrical film adaptations, particularly “Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer,” released in 1984, which is considered Oshii’s first masterpiece and one of the most outstanding works in Japanese animation history.

It was around this time that he began to incorporate his personal philosophy and aesthetics into his creations, marking the emergence of the infamous “Original Work Destroyer.” In adapting “Urusei Yatsura,” Oshii remained true to his own aesthetic style rather than the original work, and he almost deconstructed the original’s “utopian” world in terms of ideology.

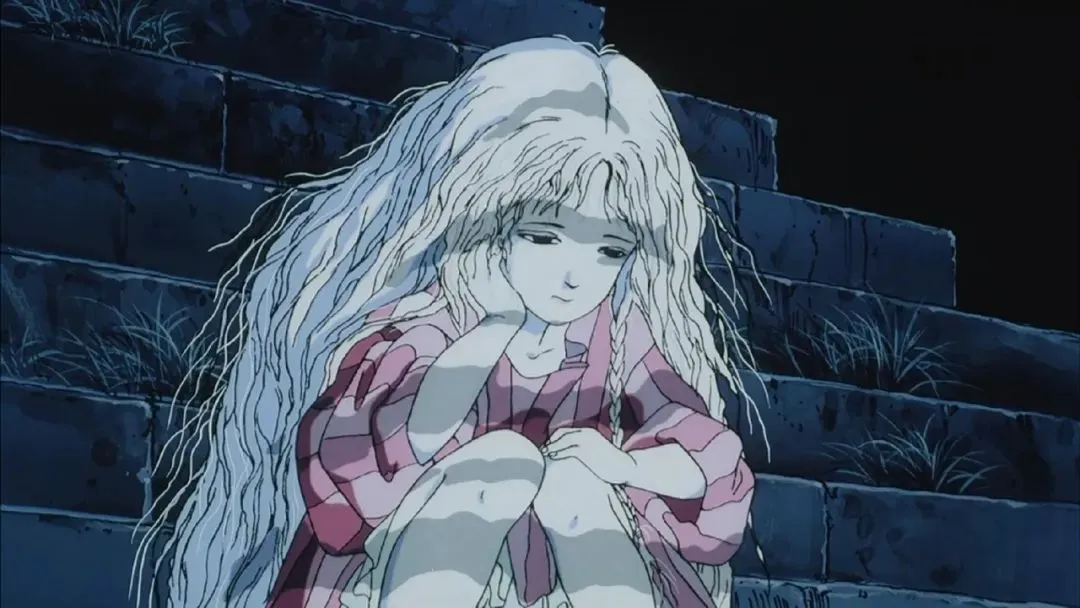

Perhaps the experience of producing commercial animation over the years had suppressed Oshii’s self-expression. His life experiences had never been about conforming to the norm. After “Urusei Yatsura,” he left his original company and followed the OVA (Original Video Animation) trend of the 1980s, producing “Angel’s Egg,” a work that was true to himself but narratively obscure. Unsurprisingly, it suffered commercial failure.

Angel’s Egg

Hayao Miyazaki, recognizing his talent, wanted to lend Oshii a hand. He offered Oshii the opportunity to direct a “Lupin the 3rd” theatrical film, but Oshii declined.

Labeled by the industry as a “director who makes difficult-to-understand films” and possessing a stubborn personality, Oshii found himself without animation projects for a while. However, he did not succumb to despair. Instead, he independently produced his own live-action film, “Red Spectacles.” It wasn’t until the formation of the HEADGEAR team and the launch of the “Patlabor” project that he returned to the animation industry.

The success of the “Patlabor” film adaptation marked another turning point in Oshii’s life. It not only re-established his position in the industry but also allowed him to take out a loan and buy a house.

To provide a better living environment for his pet dog, Oshii moved to Atami, not far from Tokyo, in 1993. Like many working professionals, Oshii began to feel the pressure of mortgage payments, leading him to plan an animation based on his forte: political themes, titled “Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade.”

At this moment, Mitsuhisa Ishikawa, a colleague from his Tatsunoko days, presented him with a proposal, asking Oshii to consider adapting it into a film.

The proposal’s cover read “Ghost in the Shell.” Oshii had read Masamune Shirow’s original manga and believed that the story was highly prophetic. Moreover, he felt that American films at the time rarely captured the presence of computers (AI) effectively. However, his heart was still set on directing “Jin-Roh.”

Ishikawa, a renowned producer in the Japanese industry, was known for his ability to outmaneuver opponents at the negotiating table with a smile. Oshii was no match for him.

That very day, Oshii was persuaded and agreed to take on the “Ghost in the Shell” project. In any case, the mortgage problem was finally resolved.

( “Jin-Roh” was later adapted into an animated film by Hiroyuki Okiura, a long-time collaborator of Oshii.)

Forging a Cyberpunk Masterpiece

The first thing Oshii did upon taking on “Ghost in the Shell” was to reread the original work about 20 times. After fully grasping every detail of the story, he began to “destroy the original.”

He established several basic principles for the story: the narrative should be driven by the protagonist’s own actions; the original’s dialogue was excellent and should be retained as much as possible; and the settings related to hackers and network technology should be further explored.

Kazunori Itō, who had collaborated with Oshii since “Urusei Yatsura,” took on the crucial task of adapting the screenplay. Whenever significant adjustments were made to the plot or details, they would consult with the original author, Masamune Shirow, who thankfully raised few objections to their adaptations.

In the final product, the story structure and character dialogue were largely preserved, but there were directional adjustments to the character’s essence and the world-building. The manga focused more on technology and social issues, while the film explored existential philosophical themes within a cyberpunk setting.

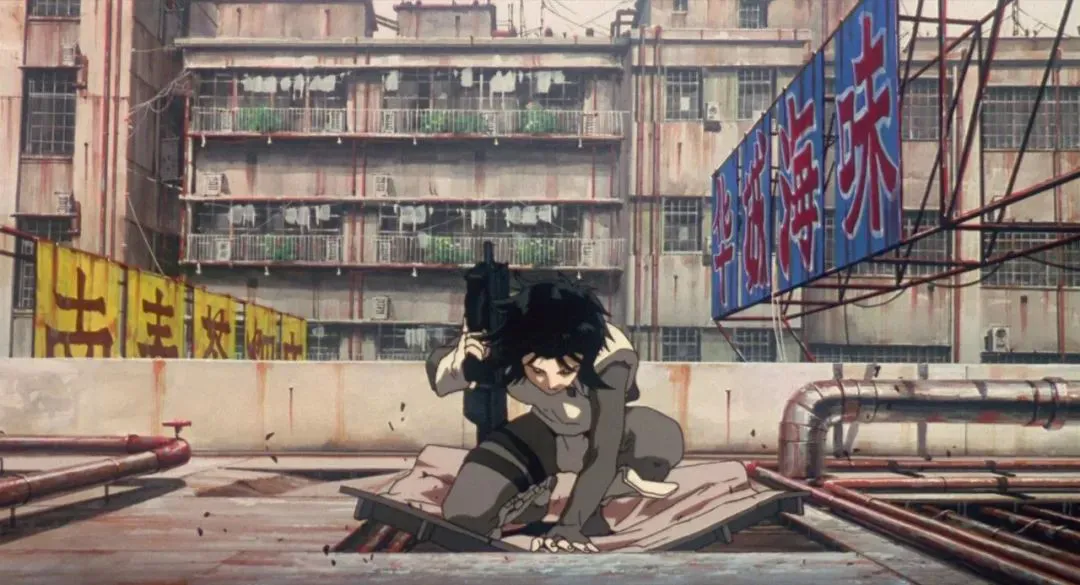

With numerous urban landscape shots, mirror imagery, low-angle fisheye lenses, and Kenji Kawai’s score, Oshii constructed a perspective that held its breath and re-examined the world. The audience’s viewpoint merged with that of Major Motoko Kusanagi, seeking an anchor for their own existence within the city’s rhythm.

In terms of detail design, Oshii was even more meticulous than most live-action films.

He researched and referenced extensively to design the characters’ sword-fighting movements. The optical camouflage combat scenes imitated the then-popular realistic fighting game “Virtua Fighter.” And all the firearms in the film, except for the one held by Batou, were real weapons that existed in reality.

This is why “Ghost in the Shell” has few action scenes, but they are exceptionally brilliant.

Counterintuitively, “Ghost in the Shell,” now revered by anime and science fiction fans, did not perform well at the box office in Japan. In fact, none of Oshii’s works have ever been major hits.

In Japan, “Ghost in the Shell” was released on a small scale in its opening week in 1995, ranking only third in the box office that week, behind the commercial blockbuster “GoldenEye” and “Haunted School 2.”

The latter has long been forgotten, but “Ghost in the Shell” has been given eternal life by time.

In 1996, with its gradual release overseas, especially the long-term sales of DVDs, “Ghost in the Shell” received critical acclaim and commercial success far exceeding its performance in Japan. James Cameron hailed it as a milestone in science fiction films, the “Blade Runner” of the new era.

Oshii’s reputation reached its peak at this time.

When the Future Catches Up

The preparation for “Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence” took nine years, with a staggering budget of 2 billion yen. During this time, Oshii also experimented with the live-action film “Avalon.”

At the time, only Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Hideaki Anno in the Japanese animation industry could command such a lavish budget to produce animation.

However, he had no intention of compromising with commercialism.

The sequel was weaker in terms of story but bolder and more radical in terms of technology. Full digital animation, 3D/2D background fusion technology, 4K resolution, centimeter-level real-scene scanning, and other then-cutting-edge production methods were all experimented with by Oshii.

The high investment resulted in a commercial lesson, with the final box office revenue only 80% of the production cost. The experiments in aesthetics, technology, and philosophy were not accepted by the public this time but have been used as case studies in the field of animation academia to this day.

Oshii, having concluded his work on “Ghost in the Shell,” has not replicated his former glory. He himself has admitted that he has, in fact, been expelled from the animation industry.

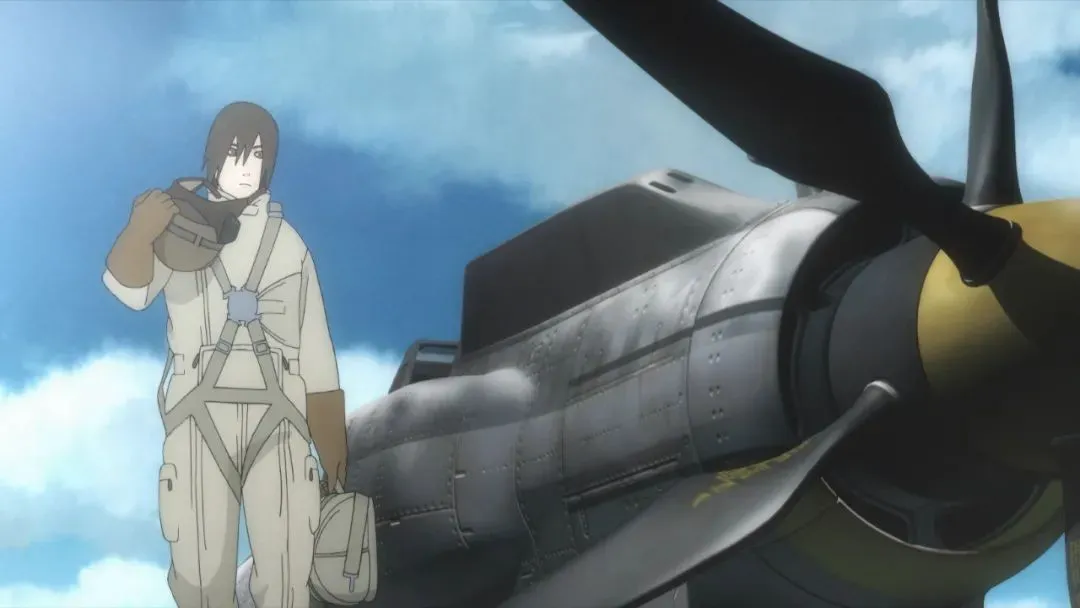

Apart from the B-movie live-action films that followed, Oshii’s “The Sky Crawlers” is perhaps the last work worth mentioning, and even that was 17 years ago.

Today, as AI is repeatedly mentioned in this era and big data consumes individuals, looking back at “Ghost in the Shell,” we realize that we have been living in the ruins predicted by Oshii all along.

-END-