The Enduring Legacy of Hitchcock’s Psycho

By Huang Xiaomi

Even if you haven’t watched Psycho in its entirety, some element of Hitchcock’s masterpiece is bound to be etched in your memory. Perhaps it’s Bernard Herrmann’s suspenseful score, Saul Bass’s iconic title sequence, or the image of Janet Leigh in her white slip, her mouth agape in a silent scream in the shower scene.

Janet Leigh

Unlike Vertigo (1958), which initially flopped and was only later recognized as a Hitchcock classic, Psycho has been celebrated from the start, captivating audiences for generations.

One of the most striking aspects of Psycho is its departure from Hitchcock’s previous suspenseful romances. The film is filled with unexpected twists, culminating in the seemingly random murder of a woman by a stranger.

Robert Bloch’s original novel begins with a “disagreement” between a mother and son at the Bates Motel. Only at the end does the reader realize that there weren’t “two” people there to begin with. The film, however, starts with Marion’s story, a red herring so elaborate that the audience doesn’t realize until halfway through that the initial theft and the police encounter on the highway are merely distractions.

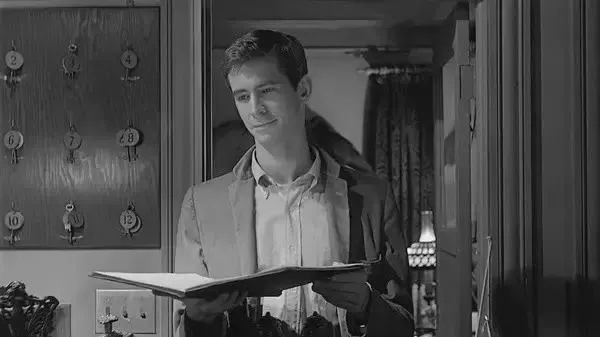

Anthony Perkins

In films like To Catch a Thief (1955) and Marnie (1964), the “bad” woman with a secret often encounters a charming, mature man (played by the likes of Cary Grant or Sean Connery) who both protects and exposes her. In Psycho, however, the neurotic Anthony Perkins is baby-faced and seemingly uninterested in Marion’s secret, only wanting to kill her.

The Bates Motel and the Old Bates House

In 1955, Hitchcock became an American citizen, marking the beginning of a prolific period in his later career. At the time, Hollywood was embracing the package deal system, and Hitchcock’s agent, Lew Wasserman of MCA, ensured that his stable of stars appeared in Hitchcock’s films. This included James Stewart in Rear Window (1954) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), Doris Day in The Man Who Knew Too Much, Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man (1956), and Janet Leigh, who was famously murdered in the shower in Psycho.

The story of Psycho can be summarized as follows: Marion, a woman from the modern city of Phoenix, drives along the highway to a modern roadside motel, only to fall into a pre-modern trap of murder.

Bates Motel

Audiences first saw the Bates Motel in the Psycho trailer. Hitchcock’s trailers were often known for their dark humor, with Hitchcock himself often making appearances. His suspense television series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, also featured intriguing introductions that piqued viewers’ interest.

However, the Psycho trailer simply shows Hitchcock taking viewers on a tour of the empty Bates Motel, revealing nothing about the plot.

Bates Motel Front Desk

The Rise of the Roadside Motel

In the 1920s, the highway network began to expand across the United States. By the 1960s, with the booming automobile industry, more people were choosing to travel by road. Motels built at highway exits quickly flourished, becoming an important part of the modern domestic travel experience.

The Bates Motel is not much different from a typical motel: a one-story L-shaped building with a front desk, rooms facing the parking lot for easy access, and clean beds, monochrome furniture, and bright bathrooms inside.

The Old Bates House

But this is not the whole picture of the Bates family. Behind the motel’s standard, modern facade lies a gloomy old house. This house, built on a hill behind the motel, is the residence of the Bates mother and son. The stark architectural contrast highlights the tension between the new and the old, life and death, and the clash between the modern ideals of the mid-20th century and the lingering Gothic ghosts of the past.

The sandwich meal between Norman Bates and Marion is the first and only encounter between these two forces. At first, Marion thinks she is dealing with a contemporary and boldly suggests that he send his mother to a mental hospital. As the conversation deepens, Marion observes Norman’s emotional fluctuations and gradually senses danger.

Norman’s room is filled with stuffed birds. He suddenly says to Marion, “You eat like a bird.” He complains about his mother’s domineering behavior while uttering the chilling phrase, “A boy’s best friend is his mother.”

Marion then leaves Norman’s room, filled with bird specimens that seem to be both dead and alive. Norman’s last words strike her: “We all go a little mad sometimes.” The unshown side of the Bates Motel prompts her to decide to return to her familiar city the next morning and confess everything.

The Bates Motel decorated with bird specimens

Perhaps some have noticed that Hitchcock remade his old film The Man Who Knew Too Much a few years earlier. In that film, the male protagonist mistakenly identifies a suspect and finds a taxidermy factory in the Yellow Pages, leading to a comical chase scene among the specimens. In Hitchcock’s eyes, taxidermy may be a form of “resurrection”—Norman turns his dead mother into a specimen, believing that she is not dead as a result.

The “California Gingerbread House”

When Hitchcock talked to Truffaut about the old Bates house, he said it was a prime example of bad, mixed-style architecture he had seen in the United States. Many 19th-century American houses were knockoffs of Victorian architecture with Gothic elements, known as “California Gingerbread Houses.”

A bed with a human-shaped depression

As the truth is about to be revealed, Marion’s sister takes everyone on a tour of “Mother’s” bedroom. In this old woman’s bedroom, in addition to a large bed with a human-shaped depression in the center, there are embroidered curtains, woven carpets, and carved washstands of unknown age. Set designer Robert Clatworthy recalled that Hitchcock wanted him to add some tacky figurines to create a strong contrast between the room and the bright white motel rooms.

Items in “Mother’s” room

Clatworthy and fellow art director Joseph Hurley mainly referenced American painter Edward Hopper’s House by the Railroad, painted in 1925. The painting depicts a white Victorian house standing in the center, its base cut off by a railroad track that runs across the foreground.

House by the Railroad

Glenn Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where the painting is housed, interprets it as a reflection of the gap and anxiety between high-speed modernization and the old American way of life. The house is lonely, making it uncertain whether anyone is inside.

The railroad tracks are also empty. Where did everyone go? Did they fall into the gap between the new and the old, unable to find a place to live? Looking back at the layout of the Bates Motel in Psycho, isn’t it a reconstruction of House by the Railroad? The old Bates house is preceded by a symbol of modern life: the motel, while the railroad tracks are replaced by the highways of the 1960s.

Nylon Bras and Printed Bathrobes

The conflict between the new and the old is also reflected in the clothing of the killer and the victim.

Psycho opens with an aerial shot of Phoenix, transitioning through several dissolves into a hotel room where Marion, wearing only a white bra, is saying goodbye to her lover.

Later, in an interview with Truffaut, Hitchcock said that while filming intimate scenes with unmarried couples was bold in the late 1950s, it was also to cater to young audiences. “If you film actors kissing again, the audience will think it’s stupid.”

Incidentally, Hitchcock’s sex scenes became increasingly explicit later on. Marnie featured marital “rape,” Torn Curtain (1966) opened with a blanket fight, and in Frenzy (1972), the actress’s white bra was finally torn off. It can be said that it all started with the lingerie flirting in Psycho.

This scene features a long shot of Marion’s back in a bra, allowing us to see the structure of the garment. The white straps and back buckle tighten Marion’s delicate upper body, with two additional auxiliary straps on each side, like a small cable-stayed bridge. Judging from the elasticity, it is likely made of synthetic material, probably nylon.

Marion saying goodbye to her boyfriend in a white nylon bra

DuPont obtained the patent for nylon in 1938, and World War II promoted its widespread use. Initially, nylon was seen as a product of technological innovation and was expensive. Later, it was widely used in clothing fabrics and gradually replaced natural materials.

The fashionable French writer Elsa Triolet even called her novel The Nylon Age (1963). Artificial materials meant new, and new things were initially associated with “good.”

Functionally, underwear is a key protection of women’s reproductive functions. Modern underwear is closely related to modern hygiene concepts. Women have historically been taught to choose underwear when they come of age, basically in sync with their first menstruation. Until the mid-19th century, young women learned embroidery from an early age. In addition to completing assignments full of letters and patterns, they also had to embroider their initials on their personal clothing. This work could not be done by servants and had to be done personally because it was private and important.

By the late 1950s, the structure of modern bras, including cups, straps, and fasteners, was mature, and underwear, like other clothing, had become a mass-produced commodity.

Modernist design entered the United States from Europe, shedding its social revolutionary implications in its native land and taking root in the New World. Streamlined designs for everyday items emerged in the 1930s, and bra designs in the 1950s followed the ergonomics and streamlined consciousness of modernist-style daily necessities.

From the underwear advertisements of the time, it seems that underwear manufacturers had exhausted all possibilities for bra styles: “push-up,” “décolleté,” “conical cup,” “strapless,” and so on.

Some may remember the former fiancée in Vertigo who sincerely loved the male protagonist. She was a fashion illustrator who specialized in drawing underwear. She enthusiastically introduced her latest work to the absent-minded male protagonist: a fluid dynamics bra “designed by Boeing engineers.”

Marion prepares to return to work

Women took off their tight whalebone corsets and put on nylon, lightweight, and easy-to-wear bras, outlining a delicate and curvaceous bell-shaped figure. The lighter bra liberated women’s mobility. Marion’s opening series of flirtations were quick and neat. Although she was still wearing a half-slip, she was undoubtedly much simpler than the previous generation of women, and she quickly packed up and said goodbye to her lover to return to work.

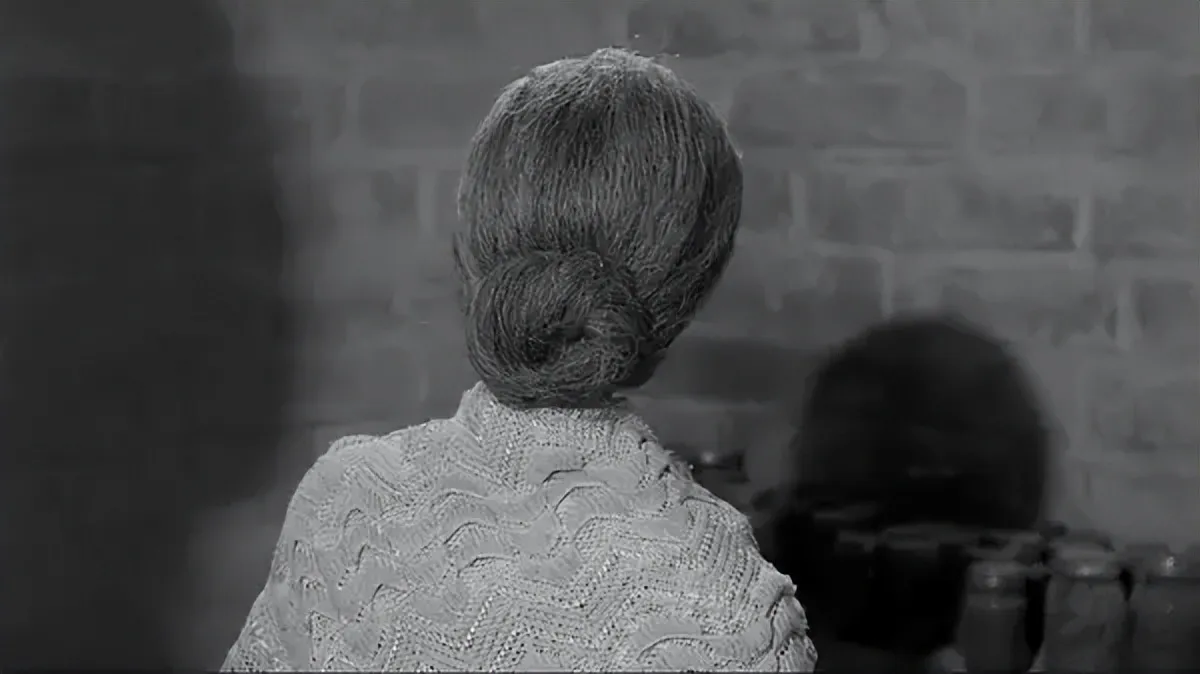

The “Mother” corpse wearing a crochet shawl

On the other hand, the “Mother” corpse in the underground storage room wears a crochet shawl, which, compared to Marion’s tight-fitting underwear, clearly implies uncleanness and decay.

The costume design for Hitchcock’s hit films of the 1950s, Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo, was entrusted to Edith Head, one of Hollywood’s leading costume designers, who served stars like Grace Kelly.

After Psycho, he strongly supported Tippi Hedren, so Edith was still invited to work on The Birds and Marnie. However, Psycho was a low-budget production, and Hitchcock only hired Rita Riggs, a designer who was participating in feature film production for the first time.

Norman wearing “Mother’s” clothes

Hitchcock wanted department store items that ordinary secretaries could afford, but Rita still took Janet to JAX, a boutique in Beverly Hills at the time, and purchased two high-end but not luxurious ready-to-wear dresses, one white and one blue. Hitchcock’s requirement for “Mother’s” clothing was a printed bathrobe, because the loose bathrobe was large enough to accommodate both men and women, so the audience would not suspect anything when they saw Norman wearing it.

Marion wears a white bra when she is having an affair at the beginning, and when she goes home to prepare to run away with the money, she changes into a black bra, creating a clear contrast between good and evil on black and white film. However, Hitchcock did not finalize whether it was white first and then black or vice versa until just before filming began.

Hitchcock and Janet Leigh in a Black Bra

The slip was on par with the bra at the time, and the former had a longer history. In the 1930s, only bias cutting could increase the elasticity of natural fabrics. By the late 1950s, as with bras, people had become accustomed to using synthetic materials to make slips, using rayon and nylon instead of the original natural cotton and silk. In addition to alleviating the discomfort of wool and other outerwear materials coming into contact with the skin, slips were more elastic and more convenient for outlining body lines.

In the hit film BUtterfield 8, which was released in the same year as Psycho, Elizabeth Taylor, who played the prostitute Gloria, wore only a slip under the offending fur coat. The tight-fitting slip probably suited Taylor very well, and the audience remembered that she had worn the same style in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof the year before.

In fact, Marion (the film version changed the heroine’s name because there was a girl named Mary Crane in Phoenix at the time) in the original novel of Psycho wore a one-piece slip. Hitchcock, however, instructed the costume designer to change the slip to a separate bra and half-slip to give Marion more room to move.

This change left us with that unforgettable back view at the beginning of the film. Even though Marion died soon after, she has been forever etched in the audience’s memory, so much so that Hitchcock was unwilling to work with Janet again after Psycho because “in the audience’s mind, you will always be that Marion.”

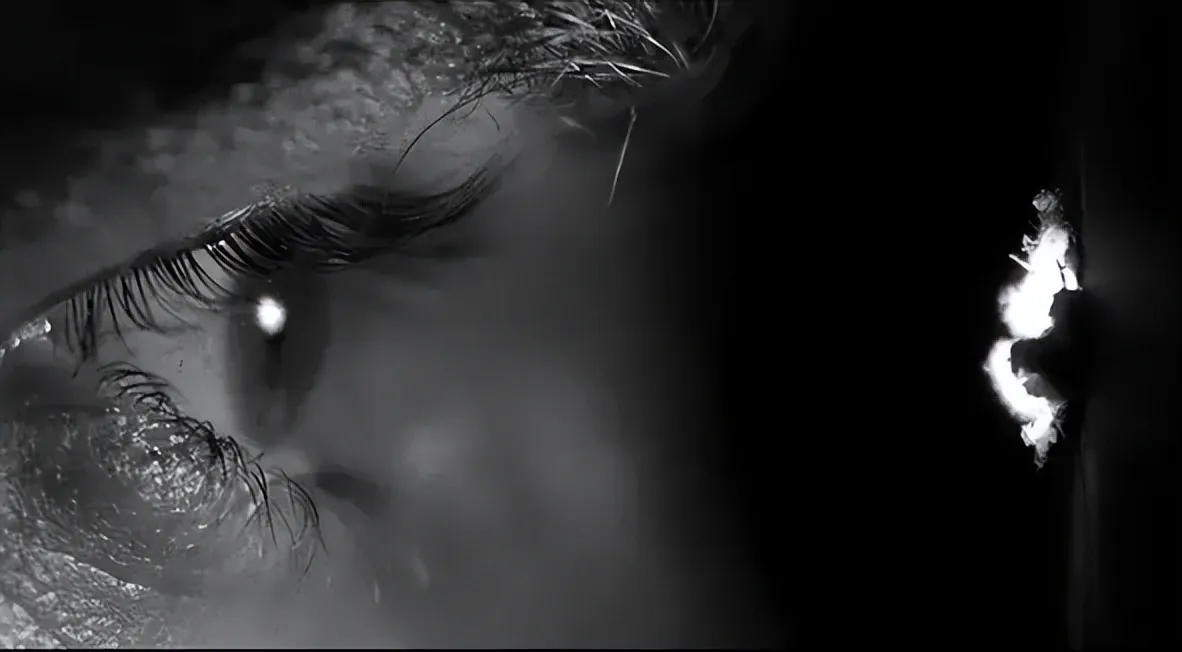

Norman Bates peeks through a small hole in his room as Marion takes off her outer clothes and walks into the bathroom wearing a black bra and slip. The camera focuses on his fluttering eyelashes. French philosopher Georges Bataille repeatedly explored the ambiguous intentions of underwear in Erotism (1957). He believed that taking off outer clothing meant an invitation, but the existence of underwear seemed to negate the previous invitation. She took it off, but she was still wearing it. However, the covered part is exactly what you expect most, and underwear becomes a further invitation. But wait, my dear. The intention of playing hard to get is really ambiguous.

Bataille believed that this was a prostitute’s skill for making a living. Catherine Deneuve in Belle de Jour (1967) suddenly transformed from a noblewoman into a prostitute. Her makeup remained unchanged, and she only took off her clothes and wore a slip to officially start her job, welcoming and sending off customers and exchanging money for goods, all relying on mastering the wearing and taking off of this “battle robe.”

Marion dies in the bathroom

In Hitchcock’s films, destroying the space for imagination often has no good ending. Marnie, who was suddenly stripped naked on a honeymoon cruise, only had hatred written on her face, while Marion died naked.

Coincidentally, there is also a motel in BUtterfield 8. In the end, Elizabeth Taylor leaves the male protagonist and drives her car onto the highway, turning into a wisp of fragrant soul. In the middle of the 20th century, threats from the pre-modern era still seemed to be distributed in various unexpected places, as if one would accidentally fall into a pit.

Next to the highway is a haunted house where people die but the building remains empty. A modern woman wearing a nylon bra dies at the hands of an “old woman” wearing a moldy bathrobe, and the car that brought her is sunk into the mire by a mental patient. The meaning of progress becomes illusory, and the more psychology develops, the greater the mental shadow it casts.

The ending of Psycho sees the killer captured, but this is not reassuring, as if things are far from being resolved, just like the buzzing fly. Psychologists are still eloquently explaining what multiple personality disorder is, leaving the audience with a vague understanding, but seeing Norman sitting against the wall, muttering to himself.