Based on Andrei Tarkovsky’s published diaries, the 1970s were a difficult period for him, filled with pain, heartbreak, and uncertainty.

In 1975, Tarkovsky’s autobiographical film “Mirror” was restricted from distribution in the Soviet Union and was not allowed to be exhibited abroad. His envisioned new film projects, such as adapting Dostoevsky’s novel “The Idiot” into a film and writing a screenplay about the life of German Romantic poet E.T.A. Hoffmann, were met with hostile censorship from the Soviet film authorities.

At one point during the decade, Tarkovsky considered abandoning cinema and shifting his focus to theater. In fact, in 1977, he successfully staged a theatrical production of “Hamlet” at the Lenkom Theatre in Moscow.

However, great works were born out of this turbulent period: In 1979, “Stalker” was released.

The Genesis of “Stalker”

Poster of “Stalker”

“Stalker” is the fifth film directed by Tarkovsky and the last one he made in the Soviet Union. In some ways (perhaps his deepest desire), “Stalker” is a film about escaping Russia: The first twenty minutes of the film, which enter the “Zone” amidst gunfire, present an imagination of the Cold War. Tarkovsky had always been concerned about the “unbearable constraints” of the bureaucracy he was destined to serve, but he also tried to stay. It was 1976 when he bought a house in Myasnoy, Russia, to take care of his wife, six-year-old son, and a pet named Dakus.

However, what happened later is well known. Tarkovsky went into exile in Western countries, creating “Nostalghia” in Italy, released in 1983, and “The Sacrifice” in Sweden, released in 1986. The director himself died of cancer in Paris in late 1986, at the age of 54.

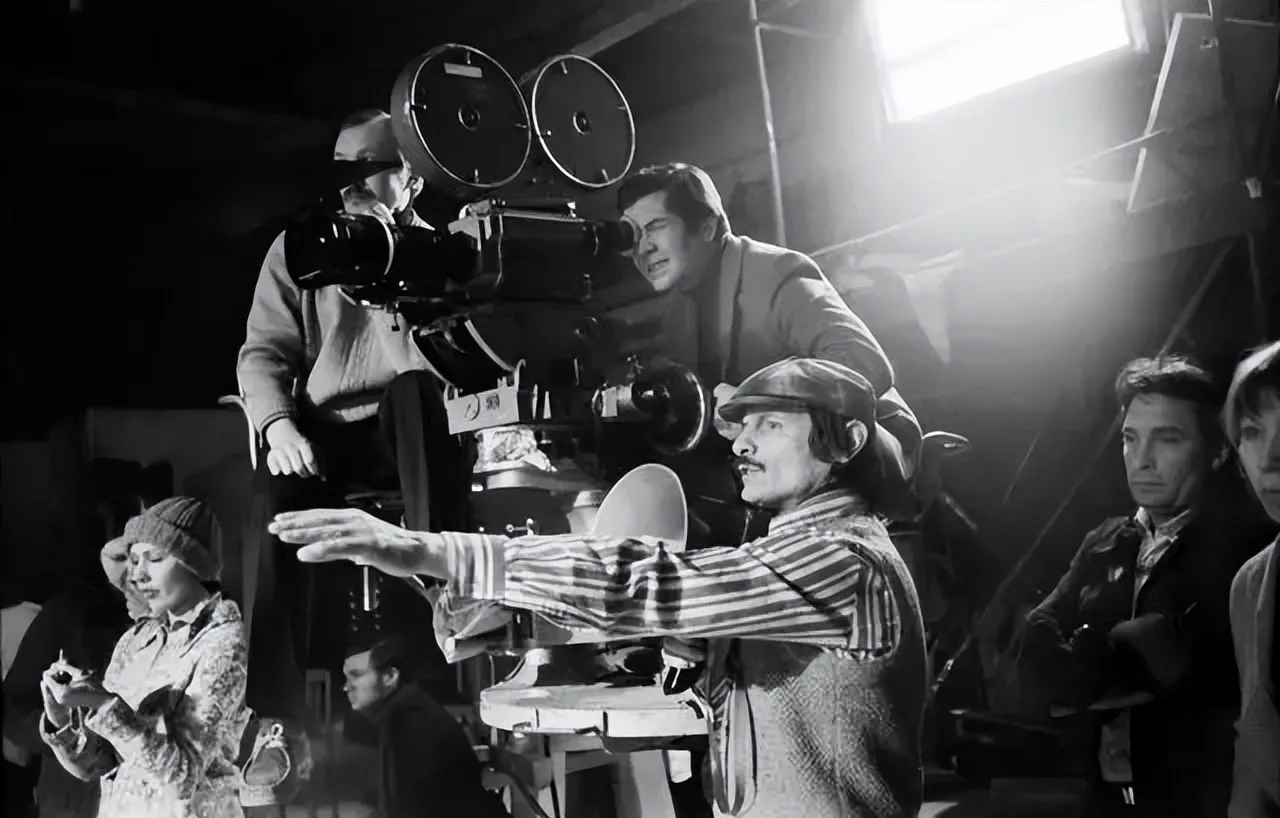

Tarkovsky on the set of “Stalker”

“Stalker” is Tarkovsky’s second attempt at science fiction, the first being “Solaris” (1972). The film is based on the novel “Roadside Picnic” by the Strugatsky brothers (Arkady Strugatsky, Boris Strugatsky), which Tarkovsky read in the literary magazine “Avrora” published in 1972. Critics were curious as to why Tarkovsky was attracted to this story—it did not have the high artistic achievement of Shakespeare or Dostoevsky’s works, and to a large extent, the story belonged to a niche area of literature; it was full of slang and violence, and was obviously not elegant enough. Moreover, it was a dystopian novel (of course, many things in the Soviet Union at that time were dystopian).

The Soul of Cinema

In his diary entry on July 3, 1975, four years before “Stalker” was completed (when Tarkovsky was still struggling to get “Mirror” released), he asked himself, “How does a film go from conception to maturity? It is clearly a mysterious, imperceptible process. The formation of a film is independent and natural, it forms in the subconscious, it is the condensation of the soul. Changes in the inner world make the film unique, in fact, only the soul can determine the formation process of the film, yet the soul cannot be consciously perceived.”

“The formation of a film is independent and natural, it forms in the subconscious, it is the condensation of the soul.”

Tarkovsky first mentioned the prototype of the idea for the film “Stalker” on Christmas night in 1974, when he wrote in his diary, “Currently, I can roughly express the novel by the Strugatsky brothers through film images, including details, uninterrupted film narration, religious behavior, intellectual transcendence, absurdity, and absoluteness.”

At the same time, Tarkovsky was reading “The Idiot” and Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” and thinking about how to adapt them. This was his way of working: multiple film projects running simultaneously, and these ideas attracting and colliding with each other in the process of thinking. In Tarkovsky’s films, one can certainly see some similarities, if not in spirit, then in the relationship between people and society.

The linguistic differences in the dialogue between the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor, as well as their mood changes, are undoubtedly the focus of the film.

Simplifying the Story

Tarkovsky simplified and adapted the story prototype of “Roadside Picnic.” For example, the book describes travelers entering and exiting the Zone multiple times, while in the film they only enter once; the Stalker’s companions—the Writer and the Professor—were actually created by the director, although the characteristics of these two characters can be extracted from multiple characters in the novel.

The linguistic differences in the dialogue between the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor, as well as their mood changes, are undoubtedly the focus of the film. People who have seen the film and people who have read the novel may have different views on philosophy or religion. Regarding “the most authentic desires in the depths of the heart,” neither the film nor the novel can summarize a consistent answer.

“Perhaps in ‘Stalker,’ I felt for the first time the need to clearly articulate that the ultimate value (love) allows humanity to survive, and its soul does not desire.”

In “Stalker,” the three set off for the Zone, their destination being a specific room where each person’s most private desires will be fulfilled. On the way, venturing forward in the strange and vast Zone, the Stalker tells them a story that seems true and false, about another Stalker nicknamed “Porcupine.” He had been to that secret room, hoping to save the life of his brother who had been killed because of his own fault. However, when “Porcupine” returned home, he found himself extremely wealthy: the Zone granted him his heartfelt desire in reality, rather than the most cherished wish in his imagination. As a result, “Porcupine” hanged himself.

Tarkovsky later wrote in his diary, “Perhaps in ‘Stalker,’ I felt for the first time the need to clearly articulate that the ultimate value (love) allows humanity to survive, and its soul does not desire.”

Dreams and Difficulties

The dreams recorded by Tarkovsky almost all took place in prison—a case occurs, imprisonment, escape, and re-arrest.

Tarkovsky had a habit of keeping a diary (which was later compiled into a book), however, even the diary cannot tell us everything, and we have to try to imagine what was not recorded in the diary. At this time, dreams are an interesting entry point. From 1974-1977, the dreams recorded by Tarkovsky almost all took place in prison—a case occurs, imprisonment, escape, and re-arrest. “Finally, as I wished, I saw the entrance to the prison, and I knew it was a prison when I saw the sign of the USSR. I was worried about being caught again, however, the horror of staying outside the prison was no different from going in.”

Although Tarkovsky’s working environment was full of difficulties, the production and shooting of “Stalker” continued. In fact, “Stalker” can be said to have undergone two creations. The 2009 documentary “Rerberg and Tarkovsky: The Reverse Side of ‘Stalker’” details the story behind “Stalker,” and as the title suggests, the documentary mainly tells the story of Tarkovsky and his cinematographer Rerberg working together, but ending their collaboration midway. It is worth noting that this documentary is narrated from Rerberg’s perspective, and the documentary turns Tarkovsky’s image into a futile, arrogant, and impatient human being.

Nevertheless, Tarkovsky’s personal image does not detract from the status of “Stalker” in film history.

Nevertheless, Tarkovsky’s personal image does not detract from the status of “Stalker” in film history.

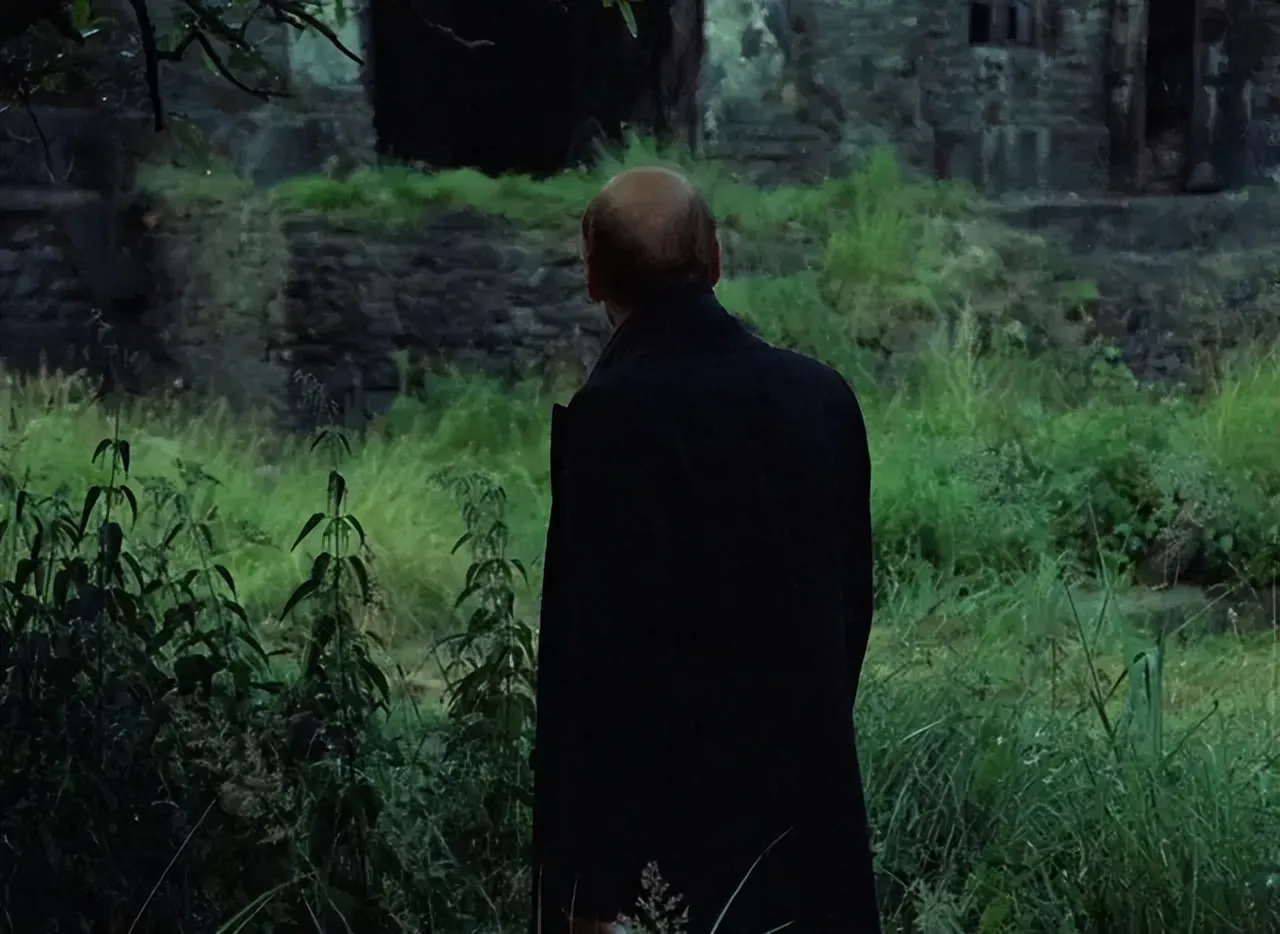

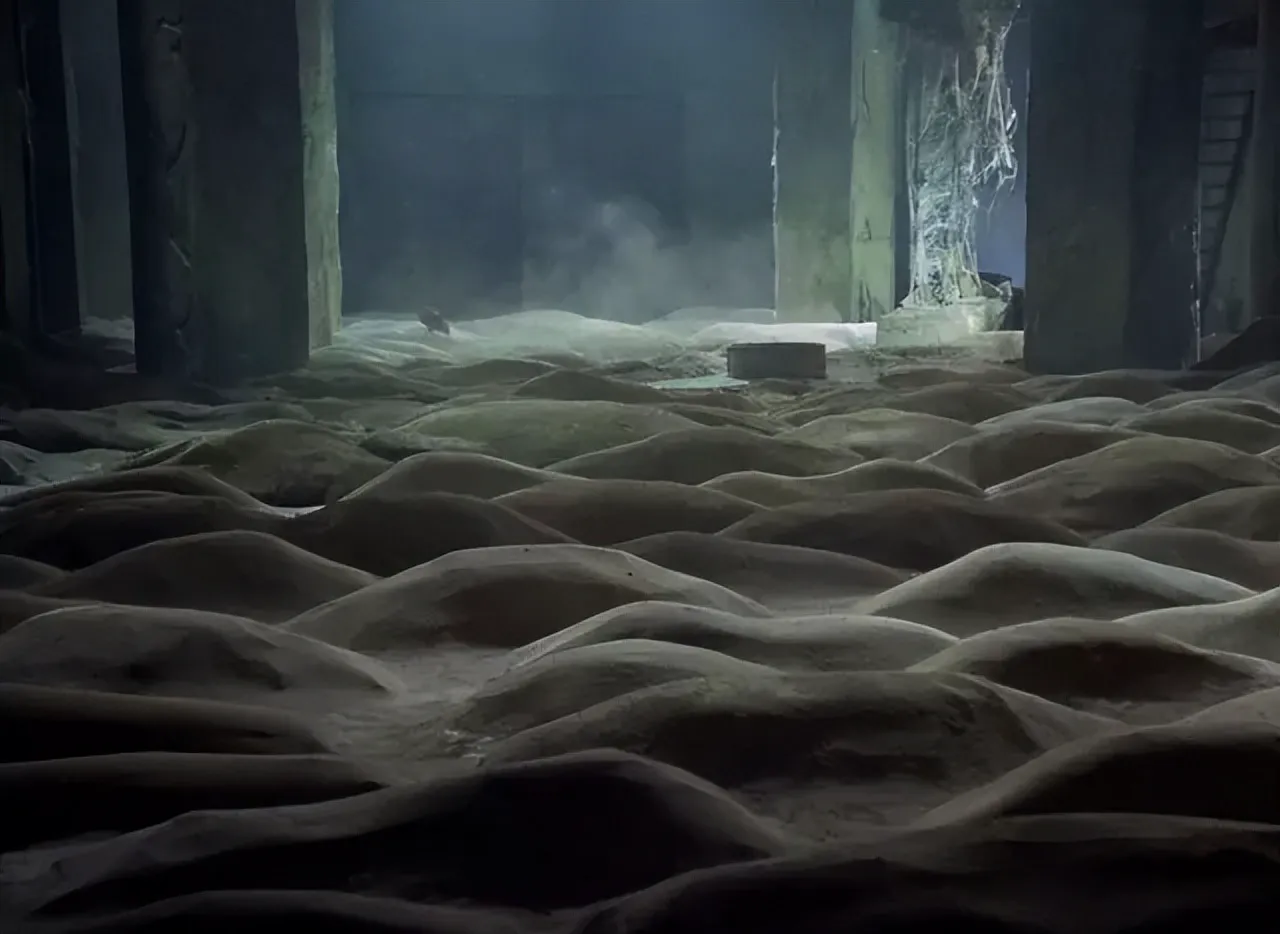

The Zone

When Tarkovsky was shooting “Stalker,” the initial ideal filming location was near the city of Isfara, a desert area in Soviet Central Asia. However, before the film was officially prepared for shooting in February 1977, a severe earthquake occurred in the area, and the director had to find a new location. This kind of last-minute change of filming location is very common in film production, however, it was not easy to find the lush vegetation, lakes, and specific landforms in the film, and the terrain occupies a very important position in “Stalker.” Some even say that this “prophesied” the Chernobyl nuclear accident a few years later.

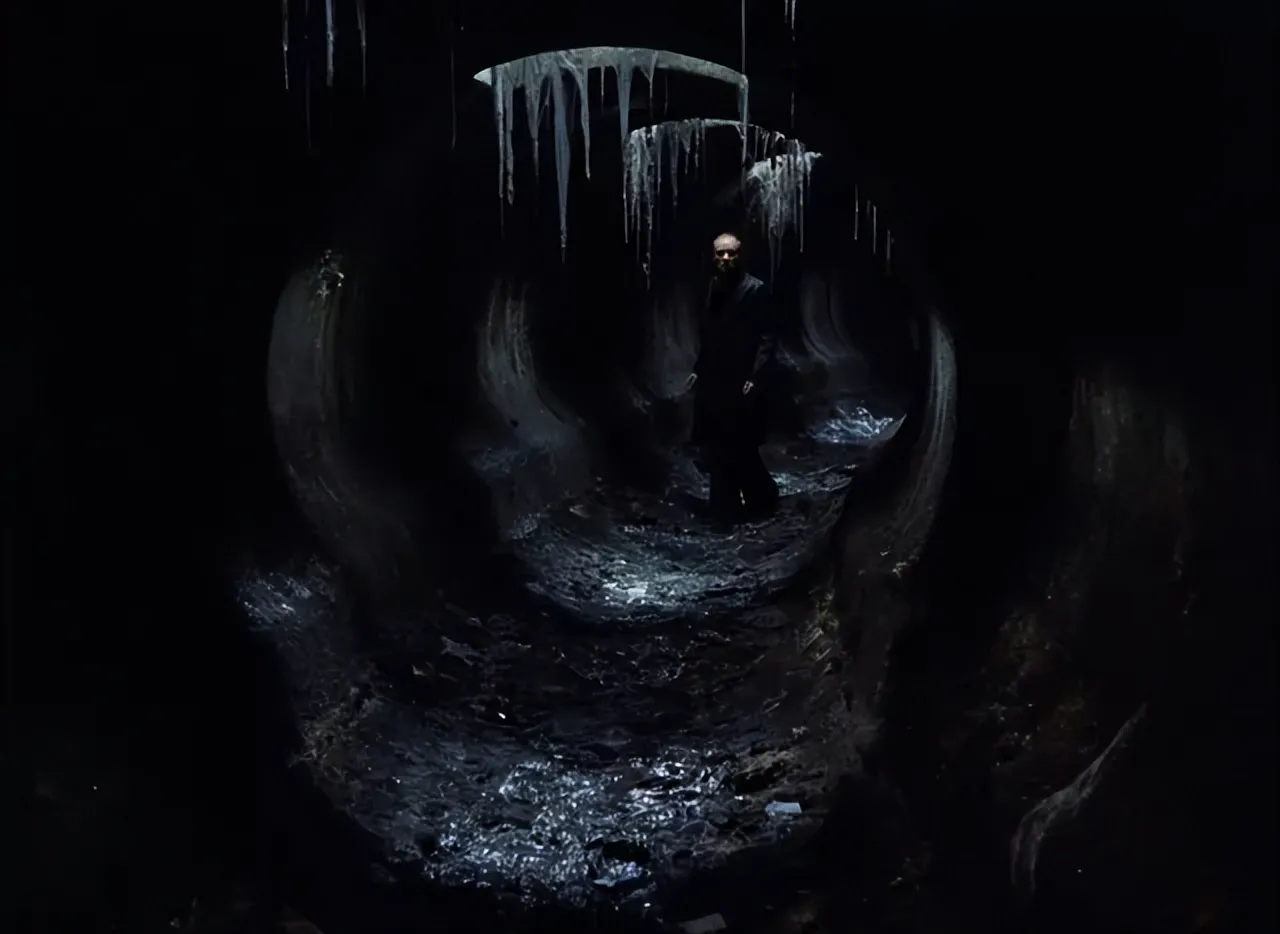

What we see is the wonderful landscape flooded by water, the pilgrimage of the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor to the Zone. However, it is not actually beautiful here.

When we watch the film, what we see is the wonderful landscape flooded by water, the pilgrimage of the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor to the Zone. However, it is not actually beautiful here, and it is even terrible for the staff working here. In one of the abandoned oil refineries, the staff had to stand inside for several hours, their knees immersed in smelly puddles, surrounded by sewage from the paper processing plant—this life lasted for several months. In the existing public information, the film’s costume designer, photography assistant, etc. have described the working environment at that time. Three months after filming, Tarkovsky replaced the film’s cinematographer, replacing Rerberg with Leonid Kalashnikov. However, the film style is so consistent from beginning to end that if we didn’t know about this, we wouldn’t think it was a seamlessly linked narrative film at all.

Before him, characters had never been filmed like this—the image presentation has both the beauty of sculpture and philosophical contemplation.

The Art of Tarkovsky

Making “Stalker” into a science fiction film allowed Tarkovsky to legally elaborate on religious issues in the film, which was not possible in “Mirror,” and great films undoubtedly have narrative freedom.

In Tarkovsky’s film language, film is not just a visual medium, the parts that are not filmed are equally important. Tarkovsky seems to have found a way to film characters—especially the freeze-frames of portraits, before him, characters had never been filmed like this—the image presentation has both the beauty of sculpture and philosophical contemplation.

Someone once asked, “Literature has developed for thousands of years, while film is still proving: can it catch up with literature, a highly developed art, in presenting the problems of the times?”

If there was ever someone who treated film as an art medium, expanding its possibilities equivalent to literature and art—I think it should be Tarkovsky.