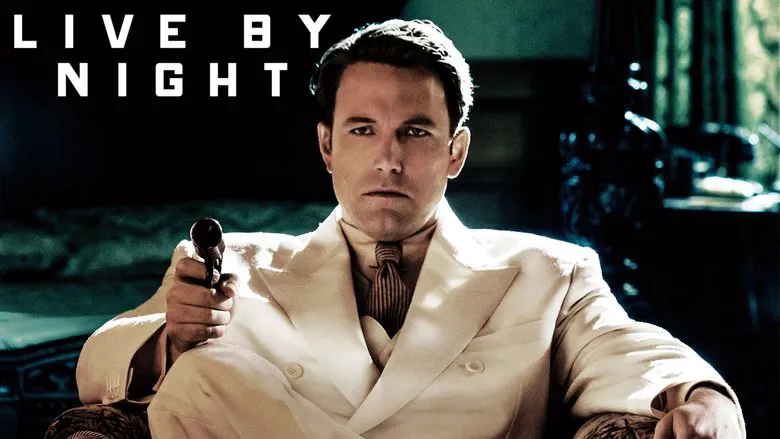

Live by Night: An American Ethnic Feud Disguised as a Gangster Drama

Delving into the past of American ethnic animosity, Live by Night presents itself as a gangster drama set during the Prohibition era.

World War I instills in Joe Coughlin (Ben Affleck), an Irish Bostonian, such a disrespect for order and authority that after his demobilization, he becomes a gangster and robber, even though his father serves as a police captain. Coughlin intends to never obey anyone again, but through his own fault, he is forced to become a member of the Italian Mafia, which sends him to Florida to organize the supply of Cuban rum at the height of Prohibition. When Coughlin’s brigade succeeds, members of the Ku Klux Klan try to seize his criminal business, as they cannot bear to see Catholics and blacks cooperating and getting rich.

The film is based on the novel of the same name by Boston writer Dennis Lehane. Ben Affleck previously adapted his novel Gone Baby Gone.

Ben Affleck’s new crime drama, in which he serves as director, screenwriter, and lead actor, positions itself as another gangster film about the Prohibition era and the Great Depression, when even good people were forced to compromise their conscience and commit bloody crimes. John Coughlin tries to kill only those who deserve it and profit only from those vices that do not seem deadly to him (he sells alcohol but does not get involved with hard drugs). He is also loyal to his loved ones, even when they betray him. Which, of course, is not the wisest behavior in an era when a gangster was required to be paranoid and ruthless.

Initially, the project was intended for Leonardo DiCaprio, but the actor limited himself to producing Live by Night.

A Crime Story Lacking Heart

However, although criminal events occupy most of the screen time, they are presented as if the director, like the main character, has no heart for them. This is neither a dashing gangster narrative reveling in the criminal hero Coughlin, nor a psychological drama like The Godfather, exploring the immersion of a decent man into a criminal hell, nor a convincing, heartfelt story about fall and redemption.

As they say in America, the picture “goes through the motions but doesn’t dance,” doesn’t put its soul into the narrative, and relies too much on plot and dialogue clichés. At times, Live by Night resembles late antique centos – poems entirely composed of lines from classical poets. Like, “all the good poems have already been written, and now we can only rearrange them in different orders.” The film has some successful moments, dramatic or funny (the picture begins very seriously but noticeably relaxes when the action moves to Florida), and it reproduces the atmosphere of the 1930s well, but as a criminal narrative, Live by Night seems like a pale imitation of more talented films. Ben Affleck does not save the picture at all. Joe Coughlin is one of his worst acting performances.

Unmasking America’s Dark Past

Why did Live by Night turn out this way? Because it was not filmed for the sake of a criminal story. The true essence of the picture is to remind viewers that America was recently a cesspool of seething and open ethnic hatred. The Irish feuded with the Italians, the Spanish despised the Cubans, all together harassed blacks and Dominicans, and white Protestants banded together in the Ku Klux Klan to keep the rest in check and prevent them from gaining power and influence.

In Russia, little is known about this, but Prohibition was inspired by Protestant fundamentalists in order to put pressure on Catholics, in whose culture alcohol played a much greater social role than in the culture of Protestants. However, the fundamentalists miscalculated – the illegal trade in alcohol gave American Catholics much more money and power than they had before. In the 1930s, a Catholic president was as unattainable a dream as a black president, and after the war, John Kennedy became president, which was perceived as an epochal event.

Live by Night pulls all this unpleasant past out into the light, forcing the characters to communicate entirely with ethnic insults and listing in detail who hates whom and why. Coughlin at one point even delivers an almost Leninist fiery speech about how the time will come when white Protestants will pay for everything they have done to other peoples, from Indians to the Irish. By the way, this time has not yet come. Maybe Affleck knows something and is warning viewers?

However, Joe usually represents not the problem, but its solution. He does not suffer from ethnic prejudices and constantly manifests this – he works for the Italians, cooperates with the Cubans, marries a black beauty (Zoe Saldana in a purely decorative role). He even, with difficulty overcoming disgust, tries to negotiate with the Klan, but its members only understand the language of lead. So the moral of the picture is not what principles can be preserved in the criminal community, but in the words from the famous song: “Brothers, don’t shoot each other, you have nothing to share in life.”