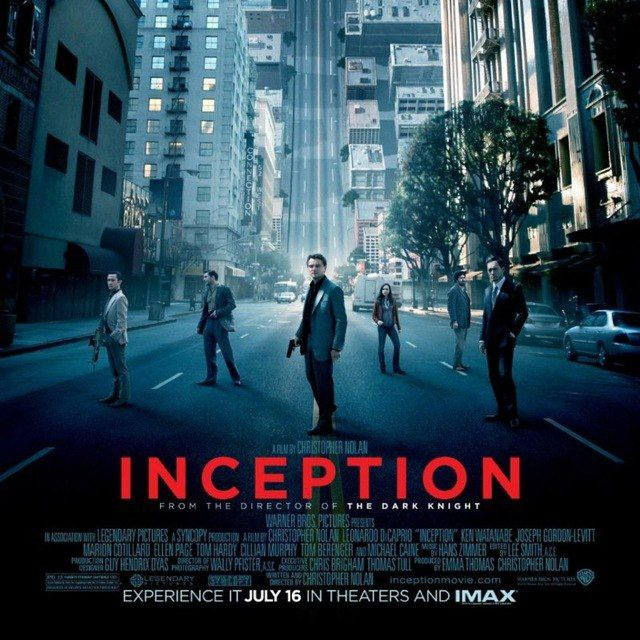

In “Inception,” Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) possesses a rare and somewhat illicit skill: he and his team of specialists infiltrate people’s dreams to extract valuable information. However, after a less-than-successful attempt to breach the subconscious of a Japanese magnate, Cobb receives an unusual assignment from the very same individual. In exchange for the chance to return to his children in the United States, where he is wanted by the authorities, Cobb must implant an idea into the heir (Cillian Murphy) of a monopolistic corporation—the idea to dismantle the corporation itself. Puzzled, Cobb assembles a team of experts: an “architect” (Ellen Page) from Paris to construct the dream, an “imitator” (Tom Hardy) from Mombasa to assist Cobb’s subtle partner (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), and a “chemist” to sedate everyone.

Legend has it that Christopher Nolan conceived the idea for “Inception” when he was 16 years old. However, it took him over two decades of practice and the success of “The Dark Knight” to bring it to fruition. The studio’s desire for a third Batman film provided sufficient leverage for Nolan to demand $200 million for an original film featuring a locomotive barreling through the streets of New York. What’s more astonishing is whether the millions were granted or that the film is likely to recoup its investment.

The Genesis of Inception

Christopher Nolan initially pitched the idea for “Inception” to the studio in 2002, but he hadn’t yet completed the script, which he intended to finish in a couple of months. It took him eight years to complete it.

Fun Facts

- In 2008, both Marion Cotillard and Ellen Page were nominated for the “Best Actress” Oscar. Cotillard won the award.

- “Inception” is Nolan’s first film since his feature debut based on an original screenplay (i.e., not an adaptation, sequel, etc.).

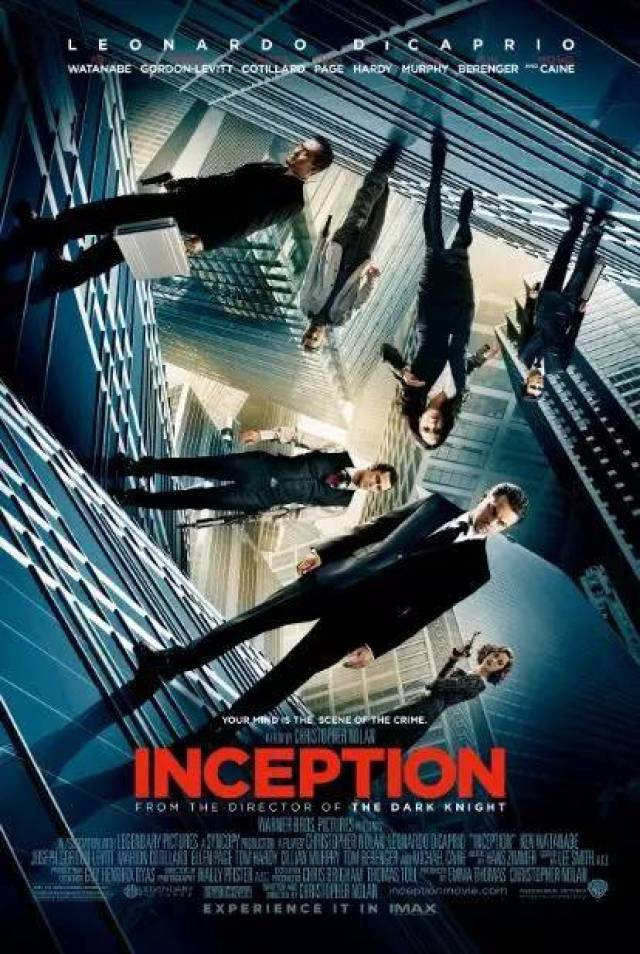

Another paradox is that this “hyper-conceptual” film, whose essence even the actors involved supposedly couldn’t grasp, turned out to be, yes, grand in scale, expensive—and surprisingly transparent. Nolan meticulously constructed the initial synopsis, creating a clear structure where there was little room for revelation or romantic speculation (except for the ending, where the choices are limited). The procedures for entering and exiting dreams are described with the precision that would make IKEA assembly instructions envious. The subconscious is depicted not as a dark sea of vague images but as a strict four-tiered structure (the characters enter a dream within a dream three times), guarded not by Freudian complexes or Freddy Krueger, but by armed individuals. “Inception,” functioning essentially as a collective “heist movie,” sees the mind-benders deceiving the unconscious using the same tactics that Danny Ocean and his crew employed to bypass casino security systems. And although the characters operate in zero gravity on one level, their ultimate goal remains the same: to crack the safe.

In addition to the armed guards, the breakers are hindered by Cobb’s deceased wife (Marion Cotillard)—or rather, her projection, generated by the hero’s subconscious. Cobb, who embodies the film’s drama, serves as an illustration of the common belief that excessive sleep is detrimental. DiCaprio, who has played characters with perception problems before and is losing his spouse for the third film in a row, not only frowns convincingly but may soon forget how to smile altogether.

In the case of “Inception,” this sacrifice would be pointless, as Nolan conceived his epic not so much to explore psychopathological depths (a rich theme, to be sure) but to showcase his directorial prowess—demonstrating his ability to synchronize three, four, or five levels of action, each with its own physical laws and time flow.

Indeed, the only criticism one can level at the director is that he spent $200 million cladding the subconscious in glass and concrete—the slabs are laid perfectly straight, and the glass gleams dazzlingly.