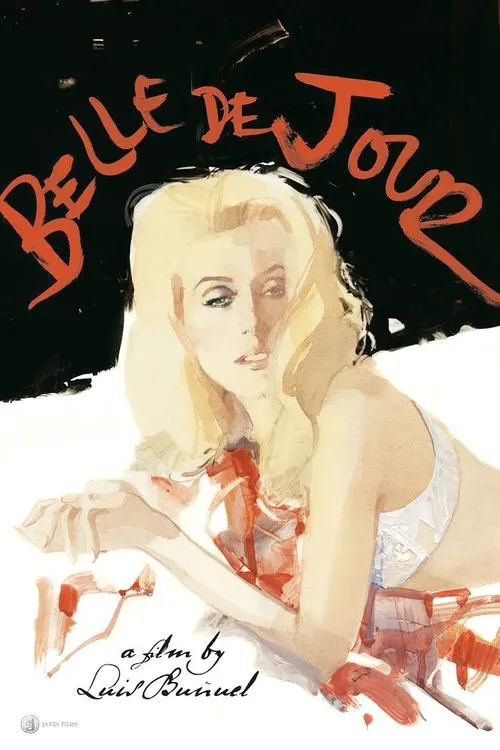

Belle de Jour

Plot

Belle de Jour, released in 1967, is a poignant and enigmatic French New Wave drama film directed by Luis Buñuel. The film is a masterful exploration of the psyche of its protagonist, Séverine Serizy, a beautiful and seemingly contented young housewife. At the center of the narrative is Séverine's inner turmoil, her desperate struggle to reconcile her masochistic desires with the stifling conventions of her married life. The film begins with visions of Séverine (played by Catherine Deneuve) in a state of domestic bliss: she is married to a devoted and handsome husband, Pierre, lives in a luxurious apartment, and has access to the finest luxuries and social status. Yet, beneath this façade of contentment lies a cauldron of unfulfilled desires and suppressed longings. Séverine's fantasies, often accompanied by painful sensations, hint at a dark undercurrent that cannot be satiated by her present circumstances. Séverine's only confidant, her friend Henri, becomes aware of her inner conflict when Séverine's masochistic impulses are revealed in a moment of unguarded vulnerability. As a consequence of this revelation, Henri introduces Séverine to Madame Anais, the proprietor of a high-end brothel. Madame Anais's establishment caters to patrons of refined taste and intellect, offering a sophisticated and discreet experience. Séverine, now drawn into this world, assumes the pseudonym "Belle de Jour," which translates to "Daughter of the Day." As she navigates this realm, she discovers a sense of release and liberation, one that complements her day-to-day existence. The role-playing that occurs within the brothel becomes a vital conduit for Séverine to express her innermost desires. It is within the walls of Madame Anais's brothel that Séverine establishes an unsettling bond with a client, known only as "the Mathematician," played by Michel Piccoli. Their encounters become increasingly provocative, with the Mathematician's fixation on Séverine bordering on obsession. His unwavering pursuit, devoid of genuine emotion, awakens Séverine to the realization that she is now trapped in a web of her own making. As Séverine strives to navigate her dual realities – her domestic life and her nocturnal exploits – the boundaries between them begin to blur. In the process, she confronts the dissonance between the life she is expected to lead and the desires that she cannot help but pursue. With the Mathematician's unwavering interest now threatening her fragile balance, Séverine is forced to confront the possibility of losing herself in this labyrinthine world. Throughout the film, Buñuel uses clever symbolism and subtle visual cues to underscore the complexities of Séverine's psyche. The setting itself often serves as a character, with the brothel and Séverine's home representing the two conflicting spheres of her existence. The brothel, in particular, becomes a site of both liberation and entrapment, where the lines between fantasy and reality are perpetually blurred. As Belle de Jour unfolds, Séverine's existential dilemmas deepen. The film's portrayal of her inner turmoil raises fundamental questions about the human condition: what are the sources of human pleasure, and to what extent do societal norms restrict our ability to express ourselves? The film's exploration of Séverine's conflicted desires, coupled with its nuanced, introspective tone, imbue the narrative with a profound sense of empathy and psychological depth. Ultimately, Buñuel's masterful direction and the outstanding performances of the cast – particularly Deneuve, who elevates the film with her captivating presence – elevate Belle de Jour to a poignant and lasting work of cinematic art. The film's enigmatic, often unsettling portrayal of Séverine's inner world has captivated audiences for generations, inviting viewers to ponder the mysteries of the human heart. In its exploration of the tensions between societal expectations and individual desires, Belle de Jour presents a searing, unforgettable examination of the intricacies of the human experience.

Reviews

Talia

One hundred minutes to convey a single spirit: wallowing in depravity. It's astounding to imagine a film tackling themes of sexual sadomasochism in the 1960s, showcasing its avant-garde and groundbreaking nature. Yet, it goes beyond just S&M; it's an encompassing critique of the self-degradation inherent within the bourgeoisie.

Recommendations