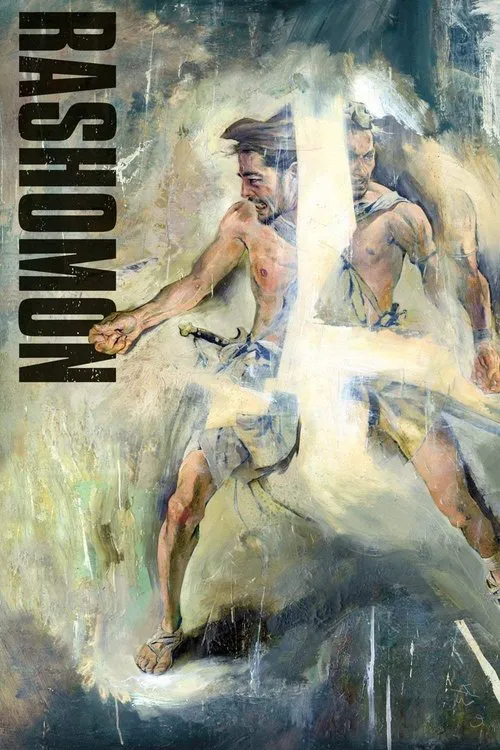

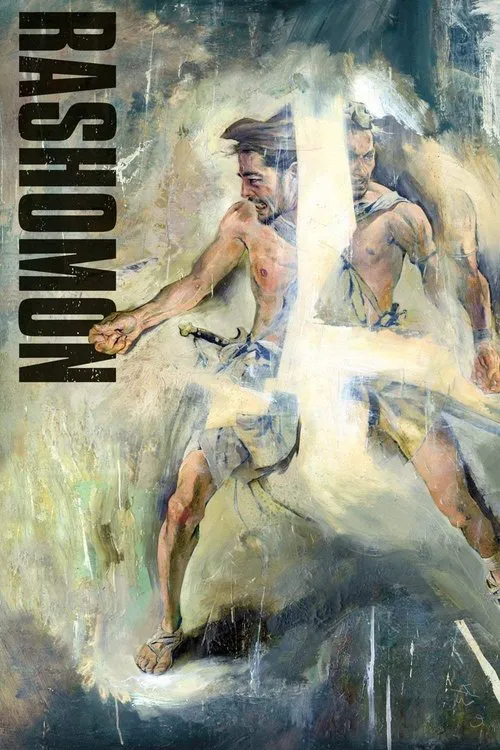

Rashomon

Plot

In feudal Japan, a traveling bandit named Tajomaru is on the scene of a gruesome crime - the murder of a noble samurai named Kōbe and the rape of his wife, Masago. Amidst the chaos and turmoil, Tajomaru encounters three other individuals, each with their own account of the events that transpired. As these three - an authoritative woodcutter, a young samurai with a penchant for honor, and Kōbe's wife, Masago - recount their tales, the viewer is presented with a dizzying array of conflicting narratives, each claiming to reveal the truth behind the events. The first narrative is told by Masago herself, recounting the events leading up to Kōbe's murder from her perspective. She describes how Kōbe, blinded by his sense of honor and morality, refused her plea to surrender to Tajomaru, instead choosing to fight to protect his wife and their honor. As the narrative unfolds, it becomes clear that Masago's tale is one of victimhood, with Kōbe's intransigence ultimately sealing his fate. She recounts how Tajomaru eventually took her by force, but that her pleas for mercy touched his heart, and he ultimately released her. However, the second narrative is that told by Tajomaru himself, whose recollection starkly contradicts Masago's account. According to Tajomaru, Masago initially resisted Kōbe's attempts to shield her, but as their situation grew increasingly dire, she relented and even encouraged him to engage in a fight-to-the-death combat with the bandit. This account paints Masago as a cunning and calculating individual, more interested in preserving her own dignity and reputation than in sparing her husband's life. Meanwhile, the third narrative is offered by the bandit Tajomaru and the woodcutter. According to theirs, Masago initially offered to surrender, provided the bandit spared her husband's life. Tajomaru, driven by a sense of compassion for the wife, agreed to Masago's demands, and in doing so, saved Kōbe's life. This account further undermines Masago's narrative, implying that she may be motivated by more complex and even duplicitous concerns than initially suggested by her version of events. Lastly, the fourth account, that of Kōbe, provides an alternate yet equally ambiguous perspective on the events. When recounting his own story, Kōbe describes how he deliberately sought to engage in a suicidal battle with Tajomaru, fully aware that the bandit's ultimate goal was to kill him. This account highlights the tension between Kōbe's adherence to honor codes and his own willingness for self-sacrifice, raising questions as to whether his death was truly avoidable. Through the multiple narratives presented in the film, Kurosawa masterfully blurs the lines between truth and fiction. Each account presents a nuanced and complex portrayal of human nature, highlighting the intricate relationships between individuals and the social and cultural expectations placed upon them. By questioning traditional notions of honor, morality, and truth, Kurosawa creates a narrative that is both timeless and timely, inviting the viewer to reflect on the nature of reality and the various ways in which stories are told and interpreted. Moreover, Kurosawa's visual storytelling, through his use of camera angles and techniques such as montage, creates a sense of dynamism and tension, underscoring the fluidity and subjective nature of truth. By juxtaposing the conflicting accounts in a deliberate sequence, Kurosawa creates a narrative that is both non-linear and thought-provoking, leaving the viewer to ponder the relative truth of each version, while also examining the larger themes and social implications of human behavior. In Rashomon, Kurosawa creates a film that is both a philosophical critique of traditional notions of truth and a poignant commentary on the social and cultural norms of feudal Japan. Ultimately, the film remains a profound reflection on the fragility and complexity of human nature, demonstrating the multiplicity and malleability of stories as they are told and retold over time.

Reviews

Recommendations